Space station tracks months-long voyages of ships at sea

ESA’s experimental ship detector on the International Space Station has pinpointed more than 60 000 ocean-going vessels so far. It has been able to follow the routes of individual ships for months at a time.

Hosted by Europe’s Columbus research module on the International Space Station (ISS), and activated on 1 June, the tracking system picks up Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals, more usually employed by port authorities and coastguards to keep tabs on local ship traffic.

All international vessels, passenger carriers and cargo ships above 300 tonnes are mandated to carry AIS VHF-radio transponders.

“AIS messages are designed to be used only on a local basis, with a range of 50 km or so to the horizon,” explained Torkild Eriksen of the Norwegian Defence Research Establishment (FFI), which built the NORAIS receiver in collaboration with the Kongsberg Seatex company.

“Instead, we are picking them up from 350 km in orbit, when they might have travelled up to 2000 km. Our receiver, therefore, had to be designed for extreme sensitivity to detect such weak signals.”

The FFI team are currently analysing results from their initial four-month phase of operations, from the start of June to the end of September. Nearly 30 million AIS messages were received from more than 60 000 different transmitters.

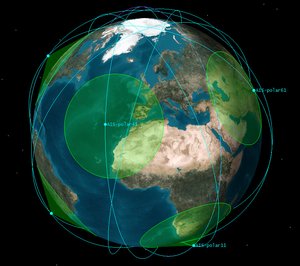

The results give an overview of the traffic of ships beneath the Station’s orbit, with coverage extending as far as polar latitudes.

“Operating from space, we have been able to track ships for long periods as they cross the ocean,” explained Andreas-Nordomo Skauen of FFI.

“Over the four-month period, we watched one ship travel from the western Pacific to Argentina then over to Europe and down to Africa, picking up its AIS signal from two to seven times per day, depending on latitude.

“So we can reveal exactly where a vessel has been in the marine environment, information that would be very useful to port, fisheries and marine authorities.

“Agencies interested in an operational version require ship detection to occur every six hours or less, so already we are not so far off.”

From the Station’s orbit, the NORAIS receiver has a maximum 4400 km diameter field of view. Signal detection is easiest when vessels are far apart in open water. In the busiest stretches of water such as the English Channel, North Sea and Malacca Straits, AIS signals swamp each other, and vessels get lost in the crowd.

“This is not a problem, however, as these particular areas are already well covered by coastal base stations,” explained Mr Eriksen. “This system’s usefulness is its global reach.”

Researchers have succeeded in detecting multiple classes of AIS signals – there are 27 in all. For ship tracking, the most important include position reports broadcast every 2–10 seconds depending on velocity, as well as the voyage report broadcast every six minutes, which includes ship destination and estimated time of arrival.

Around 2000 ‘Class B equipped’ vessels have also been detected – smaller recreational vessels equipped with less powerful AIS transmitters.

The Columbus Vessel ID System has run on a largely automated basis with weekly instructions uploaded via Norway’s national User Support Operations Centre, part of a Europe-wide network serving ISS experimenters.

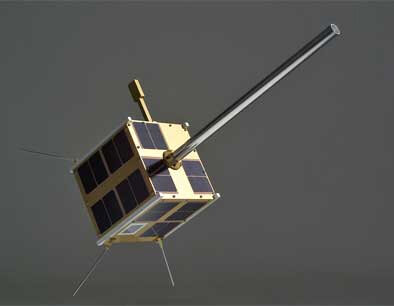

The NORAIS receiver was developed for Columbus by FFI at the same time as a national AIS-detecting satellite, AISSat-1, now in service in a higher 600 km polar orbit to focus on the Norwegian ocean areas in the high north.

The NORAIS receiver follows the same software-defined radio design as AISSat-1.

“For NORAIS, we were concerned in advance about electromagnetic interference from the rest of ISS which has become an extremely complex structure over the years,” added Eriksen. “In practice we have encountered some, but overall the receiver performance has been good.”

A grand total of 15 minutes of astronaut time was employed in mid-September to bypass a radio frequency filter originally installed because of interference fears. This enabled space-based monitoring to extend across the entire maritime radio band, including surveying two new channels set aside for a proposed expansion of AIS later this decade.

“The good news is the receiver works well in these new bands as well,” Mr Eriksen said.

“We surveyed both land and ocean, and will pass our findings to the International Telecommunications Union and International Maritime Organisation as they consider introducing these new bands.”

“This experiment is part of the In-Orbit Demonstration Programme of ESA’s Directorate of Technical and Quality Management,” explained Karsten Strauch, overseeing the project for ESA.

“The aim is to give early spaceflight opportunities to promising European technologies.

“The NORAIS receiver is one of two connected to an external VHF antenna designed for AIS detection, with the second, Luxembourg-built, receiver planned for later activation.”