Envisat Symposium Report Day 3: Satellites supporting Kyoto – our future is in our forests

The greatest single strength of Earth Observation is its wideness of view: the 10 instruments aboard ESA’s Envisat spacecraft allow scientists simultaneous looks across large expanses of our planet.

Under discussion during Wednesday’s Envisat Symposium is how researchers use this ability to peer further through time, addressing the leading scientific question of our time – the likely extent of climate change.

Human activities have been changing the chemical composition of the atmosphere, leading to an increased retaining of heat popularly termed the ‘Greenhouse Effect’.

Successfully predicting the long-term effects of this change requires enhanced characterisation and understanding of the complex processes making up the Earth System. The multi-sensor Envisat is well matched for such an aim, the Symposium heard, and has demonstrated its ability to directly measure greenhouse gases.

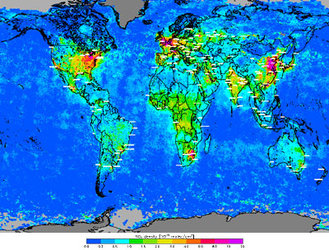

Teams from the University of Heidelberg, Bremen and the National Institute for Space Research (SRON) in the Netherlands showed how they are using data from Envisat’s Scanning Imaging Absorption Spectrometer for Atmospheric Cartography (SCIAMACHY) instrument to track trace gases in the atmosphere and produce daily global maps of atmospheric methane. Carbon dioxide is the best known greenhouse gas, but methane is able to trap more than 21 times more heat per molecule.

“Accurately characterising methane sources and distribution is very important to increase the accuracy of climate models,” said Christian Frankenberg of the University of Heidelberg. “Methane comes from natural sources such as wetlands, but human activities produce a lot as well. For example, the image shows methane given off from rice fields in the Ganges Valley in India.”

Methane is eventually broken down by chemical reactions in the atmosphere, but carbon dioxide is a longer-lived greenhouse gas. Surface vegetation stores a vast amount of carbon, only released into the atmosphere when land is cleared or burnt.

So mapping land cover and land cover change is a crucial part of climate studies, and also for implementing the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which seeks to stabilise greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels. Participating nations are given the option of planting new forests, forming ‘carbon sinks’ that can be set against their overall carbon emissions.

Peter Curran from the University of Southampton explained how he has used another Envisat instrument, the Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MERIS), to infer global levels of land-based chlorophyll – the compound that plants use for photosynthesis – enabling a calculation of the amount of vegetable biomass and the development of a new vegetation index, called the MERIS terrestrial chlorophyll index (TCI).

The results were tested for accuracy against the actual chlorophyll content of sites in the UK’s New Forest, and also compared to forest sites in southern Vietnam that were contaminated with Agent Orange defoliant during the Vietnam War.

Agent Orange leaves lasting effects on plant life, so even fully-regrown forest still has lowered levels of chlorophyll. Records of the amounts of Agent Orange sprayed on the forest between 1965 and 1971 were compared to current MTCI values, and a relationship was indeed found.

Another team from the German Aerospace Centre (DLR) recounted how they have used MERIS data to develop a vegetation index for a German brewery using it to predict barley yields. The product is compatible with a former index acquired via the US Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) instrument, but has a higher resolution.

Other speakers addressed the subject of forest mapping using MERIS, but also Envisat’s Advanced Synthetic Aperture Radar (ASAR) along with radar data acquired from Envisat’s predecessor missions ERS-1 and 2.

Shaun Quegan of Sheffield University discussed use of interferometry coherence data from the ERS-tandem mission to estimate tree age in the UK’s Kielder forest – an important variable in terms of estimating carbon flux, he revealed, because young forests in temperate regions actually emit more carbon than they take in for their first decade of life – it takes another decade to achieve a carbon 'break even'.

Growing forests are carbon sinks, but forests that are logged or burnt down become carbon sources. A team from Italy’s Tor Vergata University dealt with using radar data to detect fire damage – Envisat’s cross polarization gives it an enhanced ability to detect burn scars.

Another group from the German-based Remote Sensing Technologies has been assessing ASAR’s Wide Swath Mode to see burn scars across the vast forests of Russia – two thirds of the world’s boreal forests are sited within its borders, but they are often affected by fires.

In one vast fire east of Lake Baikal in 2003, some 202 000 square kilometres were burnt. MERIS and other optical sensors were used to home in on affected areas, then ASAR was used to peer through clouds and smoke mode, showing a successful ability to detect fire scars of up to two years old, particularly when snow melt or rainfall enhanced the signal contrast, making May to July the best time for burn scar detection.

These scientific studies show the potential of Earth Observation to support the forest reporting mandatory for advanced nation signatories to Kyoto; France has already used ASAR data to map forest coverage across the whole of French Guiana.

José Romero of the Swiss Federal Office of the Environment explained his country’s participation in a pilot ESA Data User Programme project called Kyoto Inventory, using satellite data in support of forest Kyoto reporting. Also participating are partners in Finland, Italy, Norway and the Netherlands.

“We’re interested in investigating this technology to fill in the gaps in current practices,” said Romero. “We want to learn how space-borne products can be applied to carbon reporting.”

As the Symposium heard, ESA is also carrying out a scientific project called GLOBCARBON, combining the results from all available space-based instruments to monitor global carbon flux over a seven-year period from 1997.

In addition, a forest monitoring service is included in ESA’s Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES) Services Element, addressing Kyoto reporting needs as well as serving as a tool for woodland management and monitoring environmental indicators.