Beating the battery chill factor

Maria Nestoridi, energy storage engineer

I’m a battery specialist – which means that a lot of the time I am involved in battery related reviews for various satellite programmes, ensuring that the battery proposed for a specific mission is the one that complies with the specified mission requirements.

Accordingly, I'm involved and supporting different projects from the really preliminary design phases to 'assembly, integration and testing' up to satellite launches. Acceptance and qualification testing of batteries to be uploaded to the ISS is another major part of my work, focused mainly on battery safety.

Other than safety testing, in our battery test facility here at ESTEC we perform lifetime tests for low-Earth orbit or geostationary missions, either on an accelerated basis or else testing in real time – bearing in mind some missions have a projected lifetime of more than 12 years!

Our life test conditions resemble the in-orbit satellite battery profile, encompassing their charge/discharge rates, number of cycles, the duration and number of solstice and eclipse seasons. By measuring the battery capacity at strategic points throughout the cycling we can assess how the specific satellite mission profile affects the battery degradation and overall lifetime. In this way we will be able to know the expected battery capacity left during any specific point in the mission. This also puts us in a position to know whether it is reasonable to consider a mission extension.

The other part of my job is to keep an eye on the technological state of the art, to think ahead about what we might need to develop for the future, then serve as a technical officer for the resulting research projects within programmes like TRP and GSTP. That’s what makes the work really exciting, to work with companies, universities and research institutes to try and end up with something better than the best we have today.

I have to write a ‘statement of work’ summarising the project objectives and listing the different tasks to be done, which is put out to tender, with an evaluation board selecting the winning applicant. Developing new technology can be a challenging exercise, so different entities often form a consortium in order to apply together.

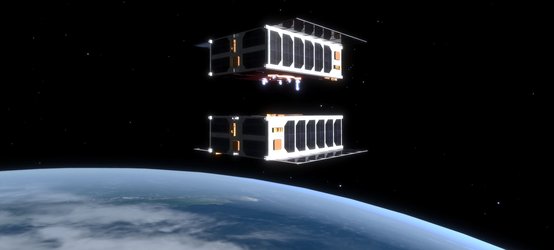

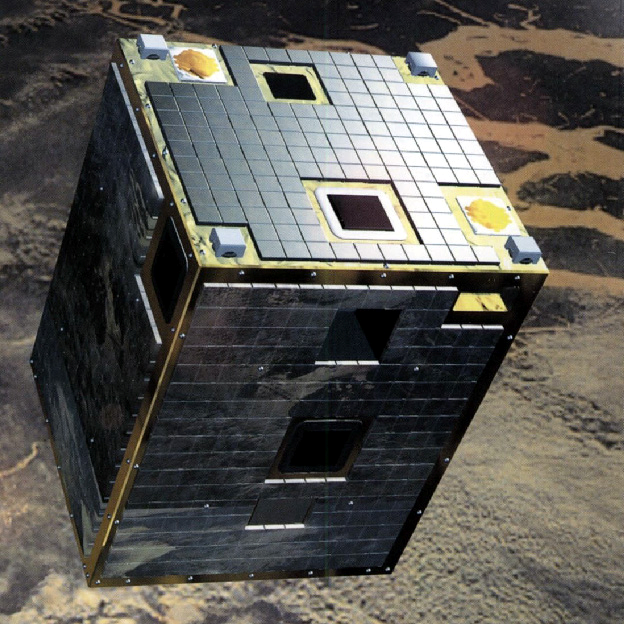

Currently, the best batteries we have are lithium-ion batteries; this has been the case since ESA’s Proba-1 satellite first demonstrated them in orbit back in 2001. They have a high specific energy, meaning high energy per unit mass ratio, and mass is all important for space. In principle these are similar to the batteries found in terrestrial electronic equipment, laptops or automobiles – space is such a niche market for the battery sector; it is really on the terrestrial side that most innovation takes place, and we try to take maximum benefit from it.

But the space side does make breakthroughs of use to terrestrial applications too. One drawback of current lithium-ion batteries is that they are best operated at room temperature – below 0°C lithium plating can take place which degrades performance and may actually trigger explosions.

One TRP project with the Democritus University of Thrace and Centre for Research and Technology-Hellas in Greece looked into breaking this temperature barrier, for future missions to cold environments, such as the Moon, or to allow a spacecraft to make a ‘cold start’. The terrestrial potential is clear too – because right now in cold countries batteries actually have to be kept heated to avoid problems.

it’s important we help our partners as much as we can, because Europe has comparatively small resources, but a success like this could lead to big things

It’s been a matter of mixing and matching candidate materials and developing others for the best performance at the end. It was at the point we ended up with similar performance to room temperature that we decided to register a patent, jointly between ESA and the University and Research centre teams.

We’re still at a relatively low technology level – we have an electrochemical system that seems to work, but we need to optimise it chemistry and also packaging wise. So that implies a follow-up project, probably with additional research partners, ideally including a battery manufacturer. We’ve been active in helping the team develop themselves, having protected their design – it’s important we help our partners as much as we can, because Europe has comparatively small resources, but a success like this could lead to big things.