The time manager: An interview with Christoph Winkler

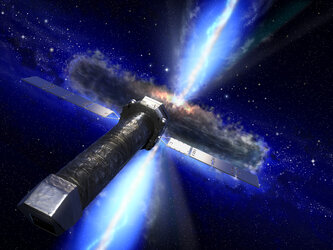

With the world’s astronomers clamouring to use Integral, Christoph Winkler is in charge of organising where it looks, and ensuring that the most sensitive gamma-ray observatory ever built delivers the best science that it possibly can.

Christoph Winkler

Project Scientist, Integral

Born: 11 July 1953 in Berlin, Germany

Having gained a Physics diploma, Christoph studied for his PhD in Astronomy at Bochum University in Germany. His extensive experience in the area of high-energy astrophysics, especially in gamma-ray astronomy, started when he worked on the imaging telescope Comptel on NASA’s Gamma-Ray Compton Observatory.

Christoph has worked on Integral for over 15 years, firstly as the Study Scientist, then since 1993 as the Project Scientist.

Christoph is widowed and lives with his two children in Noordwijk, The Netherlands. To relax, he and his family spend their time on water, in the area’s plentiful canals, rivers and lakes.

There will be nothing to beat Integral in the next 20 years and there are many things we need to study.

ESA: Please describe your role as Integral’s Project Scientist

Christoph Winkler

A Project Scientist is ultimately responsible for ensuring that a mission is doing what it is supposed to be doing. That means that before Integral was launched, I had to make sure the instruments were going to work as well as they could, by being involved in all the studies, their testing phases and their calibration.

I also had to make sure that the instruments weren’t going to be too big or too heavy, for example, so that the overall science would be degraded. After the launch, however, there is not much you can do about any of that, so my role has changed.

Naturally, everyone wants to look at different things at different times.

ESA: How has it changed?

Christoph Winkler

Well, Integral is one of ESA’s observatory missions. These are unlike planetary missions, which have a set target with instruments built to look at various aspects of that target – these results are usually of great interest to the people who designed the instruments.

Observatory missions, on the other hand, take instruments into space, and then the observations are used by the entire worldwide community of astronomers. Naturally, they all want to look at different things at different times. So my role is to execute a programme that looks at the most interesting things and optimises this return back to the scientists.

We have twice as many proposals as there is observing time, so this can be a complicated planning process. I have to take a lot of things into account. We have to subtract the time when Integral is in the radiation belt, which hampers its readings, and some sources are not visible at all times during the year.

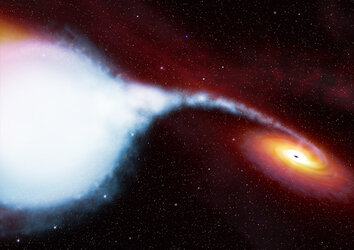

But the biggest complication is that most gamma-ray sources, such as black holes or neutron stars, suddenly flare up without warning, and thus immediately become what we call a target of opportunity.

Scientists don’t know about them until they flare up and then they ask us to point Integral towards the event. So we have to put everything else on hold, stop the observation programme we were running, and just hope that we can come back to it at a later date, once the phenomenon has been observed.

ESA: How often is the programme interrupted for these exciting events?

Christoph Winkler

We have had 10 or so such requests in the last 12 months. Once I was woken up at 3 a.m. on a Sunday morning by one request! Most of them are made during the Spring or Autumn because that is when the centre of our Galaxy is visible.

But, of course, not all requests are accepted. We have to take into account what we are currently observing and whether it is possible to go back to it. Sometimes we are under a lot of pressure for time, and we have to let people down. Integral also works closely with ESA’s XMM-Newton satellite from time to time, doing simultaneous observations. This way we can have both the wide field of view, from Integral, and the X-ray view from XMM-Newton.

My record was made in January, when Integral detected a gamma-ray burst with a duration of 60 seconds and we had the message out within 15 seconds!

ESA: Integral has also taken on another role - that of a ‘gamma-ray burst detective’. How does it do that?

Christoph Winkler

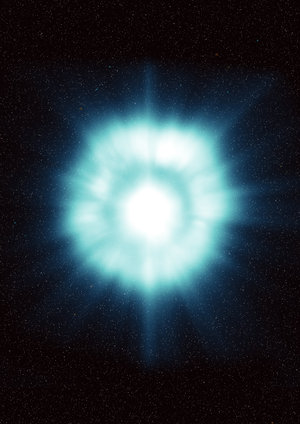

We have known for several years now that there is one gamma-ray 'burst' (or explosion) about once a day at any point in the sky, and astronomers are naturally very keen to study them, with X-ray telescopes and radio telescopes from Earth.

But the problem is knowing where and when they are going to happen. Roughly once a month, Integral may catch one of these massive gamma-ray bursts by accident in its field of view. All data captured by Integral are stored at a special data centre, and we have installed software there that automatically searches through all the data as they come in.

When it detects a gamma-ray burst, it immediately alerts the world’s astronomers via the internet. Having received the alert, their robotic telescopes can then point themselves in the right direction and focus on the explosion and its afterglow.

These bursts usually last around 20 to 30 seconds, some longer, so we have to be very quick, as scientists have to see its intensity in order to understand the processes involved.

My record for speed AND accuracy was made in January, when Integral detected a gamma-ray burst with a duration of 60 seconds and we had the message out within 15 seconds! (The error on the location was only 3 arc minutes - there have been other fast ones, but they were less accurate!)

ESA: Why do we want to study such phenomena?

Christoph Winkler

I think it is a natural interest for humans to find out more about things that they don’t understand. When you detect a huge explosion occurring in your own galaxy, it is normal to ask what it is.

Every time we find a starburst, we have to link it up to what we already know about galaxies. This sometimes helps us improve our models, and at other times contradicts everything we thought we knew.

There will be nothing to beat Integral in the next 20 years and there are many things we need to study in the future, improving our gamma-ray map of the galaxy, and showing how many stars have exploded in recent history.

Of course, I feel that it is a great privilege for me to be able to study these things in my career.