Wind satellite survives vacuum

ESA’s Aeolus satellite has been particularly tricky to build. One of the main stumbling blocks has been getting its lasers to work in a vacuum, but recent tests on the satellite show that the vacuum or temperature of space won’t get in the way of Aeolus measuring Earth’s winds.

Aeolus carries one of the most sophisticated instruments ever to be put into orbit: Aladin, with two powerful lasers, a large telescope and very sensitive receivers.

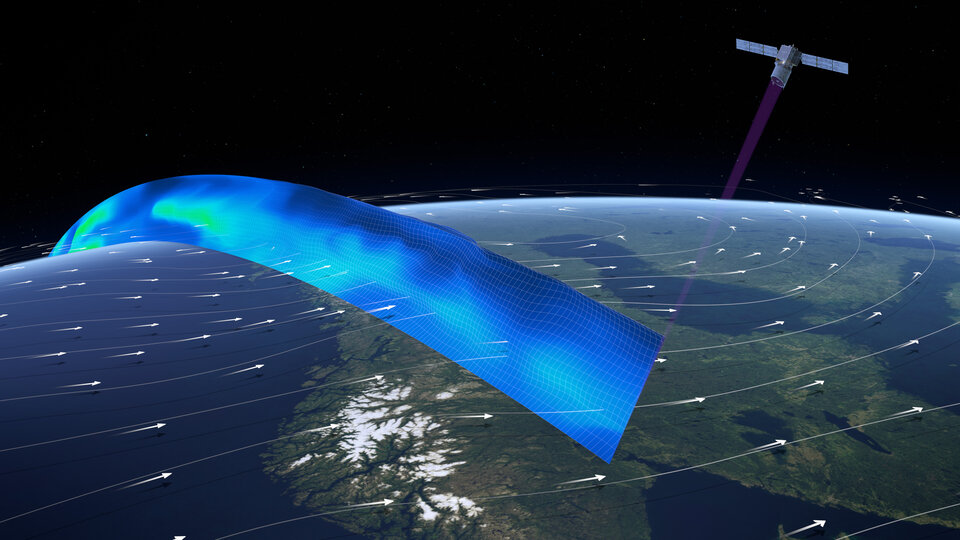

It shoots pulses of ultraviolet light down into the atmosphere and measures the backscattered signals from molecules and aerosols to profile the world’s winds.

“This will be the first time that we will be able to directly measure profiles of the global wind field from space in cloud-free conditions. It has been a major challenge for us all – our ESA engineers, industry, our Member States – to overcome many technical and programmatic challenges.

“I am grateful to everyone for having gone through this and for having trust in ESA to finally make it happen. We are now very close to seeing the fruits of a long endeavour,” said Josef Aschbacher, ESA’s Director of Earth Observation Programmes.

These vertical slices through the atmosphere, along with information on aerosols and clouds, will advance our knowledge of atmospheric dynamics and contribute to climate research.

Since Aeolus will deliver measurements almost in real time, it is also set to provide much-needed information to improve daily weather forecasts.

The satellite’s novel technology was under development for some years, but issues with the laser component of the instrument and with the optics, which have to survive exposure to the high-intensity laser pulses, were eventually resolved, and in 2016 the instrument was finally ready.

Aladin was then added to the satellite in the UK, after which the assembly was moved to France where it was shaken to simulate the rigours of liftoff.

The last round of tests was carried out in Centre Spatial de Liege, Belgium, and involved putting the satellite in a thermal–vacuum chamber for almost two months.

Once the satellite was safely inside, the air was pumped out and the chamber cooled by liquid nitrogen to simulate the environment of space – and then Aeolus was put through its paces.

ESA’s Aeolus project manager, Anders Elfving, said, “The test was exceptionally complex, not only because it was a tight fit with the satellite filling up most of the space in the chamber, but also because we had to make sure that the whole instrument’s performance is tip-top.

“It was an extremely technical and delicate undertaking that included firing Aladin’s lasers at full power.

“The satellite as a whole came through with flying colours, and we are particularly pleased that the two laser transmitters performed brilliantly.”

With this milestone behind it, Aeolus has now been returned to France where it will have a few final tests before being shipped across the Atlantic to Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana for launch on a Vega rocket in the autumn.

Aladin was built by Airbus SAS in Toulouse, France, the satellite by Airbus Ltd in Stevenage, UK, and the laser transmitters by Leonardo SpA in Florence and Pomezia, Italy.