Interview with ESA Director General Jan Wörner, by contemporary artist Aleksandra Mir

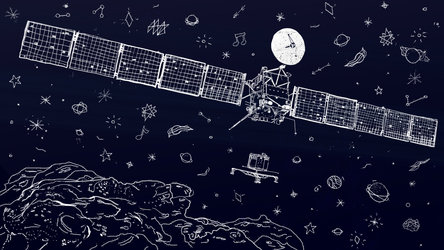

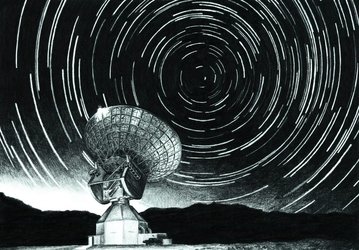

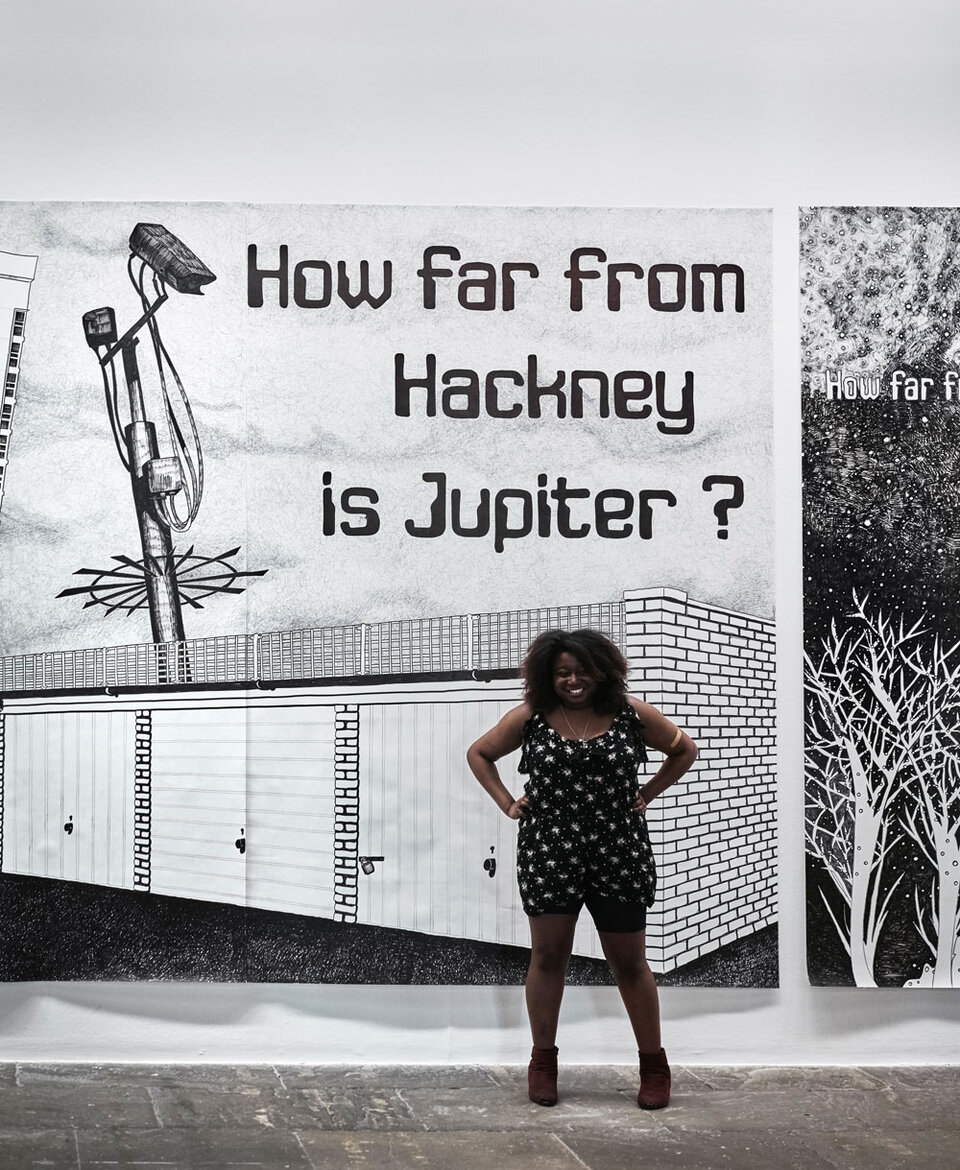

Inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry and the anonymous artists who depicted Halley’s Comet in 1066, contemporary artist Aleksandra Mir has created her latest work Space Tapestry, which tells an episodic visual story of space travel.

Over the past three years, Mir has formed relationships with professionals in the space industry and academia who have informed and inspired the Space Tapestry, including ESA’s Director General Jan Wörner. The work draws out themes relating to current debates, recorded events, scientific discoveries, technological innovations and predictions of an imagined future that currently affect all our lives.

In the United Kingdom, both the Modern Art Oxford and Tate Liverpool have presented chapters from Mir’s latest work. Between 23 June and 15 October, The Tate Liverpool hosted Space Tapestry: Faraway Missions. The Modern Art Oxford is now hosting Space Tapestry: Earth Observation & Human Spaceflight until 12 November 2017.

Mir interviewed Jan Wörner earlier this year as part of her project...

Aleksandra Mir: I was very impressed when I first heard you speak about Space 4.0. Where I'm coming from, the art world, we divide our art history in periods. We have the Classical and we have the Modern and now the Modern is over 100 years old. So we have Modern Classics. It gets very confusing.

We also have museum departments struggling with the preservation of ageing New Media. I'm a Contemporary artist, but watching myself ageing, I can easily tell that the Contemporary is not going to last forever. Calling my work Art 1234.5 Version b would be more practical. How did you come up with the idea of using decimals to describe the periods of Space history?

Jan Wörner: Some people still use Old Space and New Space for what they believe is the difference between early exploration and the era of commercialisation, but that is already a 30-year-old story. I never used it. Space 4.0 is something entirely different. I make distinctions between Space 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 and 4.0.

Space 1.0 is ‘early astronomy’. Space 2.0 is the ‘Space Race’. Space 3.0 is the opening up of different applications, such as Earth observation and navigation. And now we are entering the phase of Space 4.0, which means we have totally different actors: not only two superpowers going into space, but also over 70 spacefaring nations worldwide.

Space 4.0 is our day-to-day infrastructure with telecommunications, exploration and science. Space 4.0 is also commercialisation and participation, meaning that, in the past, the governments or the agencies of the superpowers decided what to do. Today and in the future, more and more people are using space and will be directly influencing space. Therefore Space 4.0 is not about a new space, but looking to the future and a new world.

AM: As an artist, of course I'm very interested in finding out how the Arts and Humanities can play a role in this evolution.

JW: When I talk about the fascination of space, I'm not restricting it to STEM (science technology, engineering and mathematics) but I say STEAM, where the A stands for art. There are a lot of examples where artists are using space as a part of their work. Questions raised by studies in the space domain can provide inspiration for artistic exploration, which in turn can offer fresh perspectives on the science.

In my former job, I was the head of the German Aerospace Centre. We invited artists to participate in parabolic flights and to use microgravity for their own activities in art and music. At ESA we have worked with the French urban artist, ‘Invader’, who applied his special brand of Space mosaics at different ESA sites, and with the composer Vangelis for his latest music album ‘Rosetta’.

We’ve worked with photographers such as Edgar Martins and Frans Lanting, and contributed to many exhibitions around Europe. We operate artist-in-residence programmes, where artists work at ESA sites alongside their technical and scientific counterparts, in innovative areas such as interactive art, sound art, animation, film and visual effects, hybrid art or performance and choreography, for example.

The humanities also include history, so we should not forget our History project. This aims to record the European collaborative space programme from its beginnings in the late 1950s to the present, as well as finding creative ways to tell a modern-day audience about the fascinating achievements of days gone by.

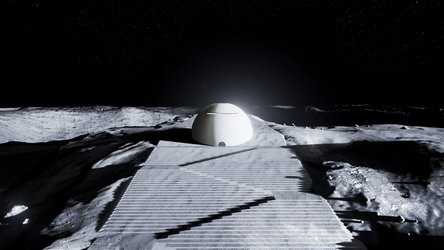

AM: You have a vision for the Moon Village, which I understand is not a literal village on the Moon.

JW: The Moon Village is where different interests come together, where one tries to have a joint understanding of doing something together. It is a concept, not a project. And the concept is not a single concept. It is not a plan for an end. It is not a fully fixed thing. It is an open architecture, an open idea, allowing access from very different players, whether they be robotic or human, whether a company or the public, whether individuals or the spacefaring nations.

AM: Anybody can basically assign themselves to this project?

JW: Yes.

AM: There is no restrictive committee?

JW: No.

AM: I did a project 17 years ago called, The First Woman on the Moon and if you Google, ‘Who was the first woman on the Moon?’ you still get my name I'm sorry to say. Of course, it keeps me very busy but it is also a bit embarrassing on behalf of humanity that you are now sitting here with an artist and not an astronaut who has this title. In 2014 I heard at a conference in London, David Willetts, the former UK Science Minister, make an educated guess that the first woman on the Moon would be Chinese. I realise that gender politics is not a reason to launch a Space mission but I am just very curious, why would ESA not take the opportunity to make her, say French, even as a PR exercise?

JW: We have female astronauts in Europe. One is sitting in an office above me here in Paris right now: Claudie Haigneré is French. We have Samantha Cristoforetti from Italy, and in Germany they are now also looking for a female astronaut. I don’t think this a gender competition. I think what David Willetts wanted to say was, 'Be aware, China is very rapidly taking its opportunities in space. They are very successful and maybe they are also soon going to send humans to the Moon.'

AM: There is a symbolic value in making the point of the woman?

JW: Yes but, for instance, consider the image that the ESA created for the Aurora Exploration Mission, which was a human spaceflight programme to explore the Solar System, it shows a spacecraft and a female astronaut. So yes, we are aware, but I don't think that it matters whether it is a woman or a man, or British, German or Italian who will be the first. For me, it is not about the competition at all.

AM: If you listen to the young generation now, they want gender fluidity and advanced medical science together with shifting popular opinion is already making that possible. So if we wait too long in sending a woman to the Moon, it might not be a man or a woman. It might be something completely different. In your vision of the Moon Village, is there going to be a population of some kind?

JW: It may happen, but the Moon is not a very nice place to stay because you have very long nights. From that perspective, it is not the best environment for humans to be in for any long period of time.

AM: Well nothing beyond the Earth is, really? I mean, is there a reason for us to leave at all?

JW: Yes. It is in our genes to leave and to explore new worlds. People climb Mount Everest. Is there a need to climb Mount Everest? No, there is no necessity but it is in our genes to discover the unknown.

More information

The Modern Art Oxford is now hosting Space Tapestry: Earth Observation & Human Spaceflight until 12 November 2017.

More about Aleksandra Mir's space artwork at: https://aleksandramir.info/projects/space-tapestry/#1362

Aleksandra Mir's book, 'We can't stop thinking about the Future: Aleksandra Mir Speaks with the Space World', is published by Strange Attractor Press, London, 2017, and available here: www.aleksandramir.info