Sharper images, better blades

Software developed to handle distortions in satellite images is now bringing the search for cracks in wind turbines into the 21st century.

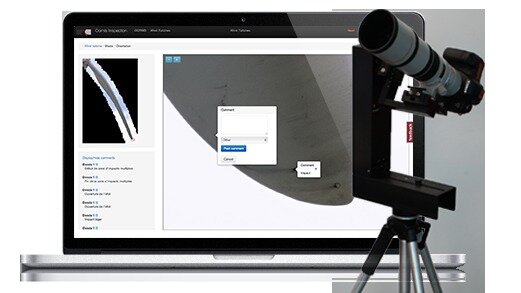

This past winter, using a new system built around software developed for space, the French company Cornis inspected 100 wind turbines in France. A turbine's three blades can now typically be scanned for problems in less than two hours – far faster than traditional inspection methods, which can take up to a whole day.

And instead of climbing on the blades and working at risky heights, inspectors can now safely do the job directly from the ground.

As Thibault Gouache, CEO of Cornis, explained, it is not possible to inspect turbine blades during the winter using standard manual techniques: “The days are too short, and the winds and cold make it impossible for climbers.”

But the new approach changes that. For the first time, wind turbines can be inspected for cracks and monitored to track how well they are ageing, year-round, simply by snapping a few photos from the ground.

Space software was the solution

The key to the technology is an algorithm that was created by M Gouache’s business partner, Baptiste Coulange, to analyse images taken by satellites.

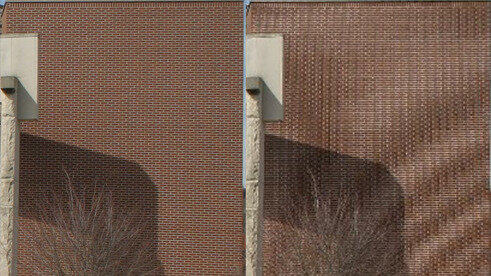

This algorithm detects ‘aliasing’, a distortion that can be a serious problem for scientists trying to interpret images.

Anyone who uses digital images is familiar with aliasing.

It occurs when you zoom in on a group photo of business colleagues and notice that their vertical pinstripes suddenly run horizontally.

Or, you might see it if you enlarge a photo of a face, and instead of a smooth, curving cheek, see strange, boxy steps appear along the edge.

With satellite images, aliasing can occur anytime a picture is taken of regular, repeating structures, like cars in a parking lot, or rooftops.

“You’re trying to identify fine details on the ground. If you’re looking at an oil and gas plant, it has very repetitive lines,” said M Gouache.

“All those pipes can be deformed, in an image. If you want to better understand how the gas plant is set up, you’ll have problems.

“Here, Coulange’s algorithms can help. If there’s a little aliasing, we can detect the problem so we can deal with it.”

Space spin-off: a business opportunity

While Coulange developed the aliasing algorithm to handle satellite images with support from France’s CNES space agency, M Gouache worked at ESA’s Technology Centre, ESTEC, in the Netherlands.

Together, they formed the French start-up company Cornis. With Cornis, they wanted to put expertise and technologies garnered from space programmes to use in terrestrial applications. Their first target was the wind energy industry.

“What we found was people in the wind industry had a lot of needs, in terms of monitoring wind turbine blades,” said M Gouache.

“Wind turbines and, in particular, their blades are subject to wear and tear due to all year round, thanks to weather exposure and continuous vibrations.”

The core technology had proved successful in improving image quality in space – it was tested on images from the SPOT, Pléiades, Quickbird, WorldView2 and GeoEye satellites.

Now, Cornis thought, it was time to try it on wind turbines.

“Cornis’ use of a special space algorithm to help the wind turbine industry is a good example of how developments in our European space programmes can help other industrial sectors,” said Claude-Emmanuel Serre from Tech2Market, part of ESA's Technology Transfer Programme network of technology brokers.

“Turbine blades are made of composites which are subject to cracks. Cornis’ technology coming from space programmes will be a great help to the wind turbines industry.”

Wind blade inspection

“The wind industry was using a hodgepodge of manual solutions to keep track of their blades,” M Gouache said. “Some had people going up and down, to check. Others tried to take pictures. There was no systematic scanning or screening.”

Cornis built a new product, using their space knowhow to develop a consistent and very reliable inspection system.

Using a high-powered camera to take pictures, they were able to digitise the blade surface.

These pictures had to be very precise, with no blur, in order to show the smallest cracks or fractures. Of course, without this algorithm, less blur could often result in more aliasing.

“If you’re not very careful, you will erase the small cracks and defects the wind industry is after. They want to catch them as early as possible,” M Gouache noted.

Using algorithms similar to those they developed for satellite images, Cornis’ technology is able to identify distortions caused by aliasing and correct to limit the aliasing.

“This allows us to extract and keep all the fine details.”

On the market for almost two years, their blade inspection technology keeps track of all changes in the surface of the blades throughout a wind turbine’s life.

Clients say the technology is game-changing.

“Cornis’ solutions will be key to addressing an overwhelming need for wind farms traceability and age tracking,” said a spokesperson for EoleRes, a subsidiary of the RES Group, which develops, builds and operates renewable energy production units in Mediterranean countries and the Middle East.

Cornis’ main customers are large utility companies like GDF in France, Italian energy company Enel, UK-based renewable energy company RES Group and the two wind farms operators, EDF and EDPR.

Turbine manufacturers are also showing interest. In fact, Cornis has already inspected blades for Germany’s Siemens and France’s Vergnet.

Depending on the turbine, either the manufacturer or the electric company is responsible for maintenance.

“What we do for each is very, very similar,” said M Gouache. “Though what they do with the information might be different. Manufacturers might use the information to better understand which blades are ageing faster, while utilities might compare between manufacturers, looking at which ones are more reliable.”

In coming months, the company plans to inspect another 100 turbines in France and, recently, they also launched inspections of offshore wind turbines in Denmark and Germany.

“It’s like a kid’s dream, it’s fun out there,” said M Gouache, of his first boat trip to inspect offshore turbines. “It’s quite new for us, very interesting.”