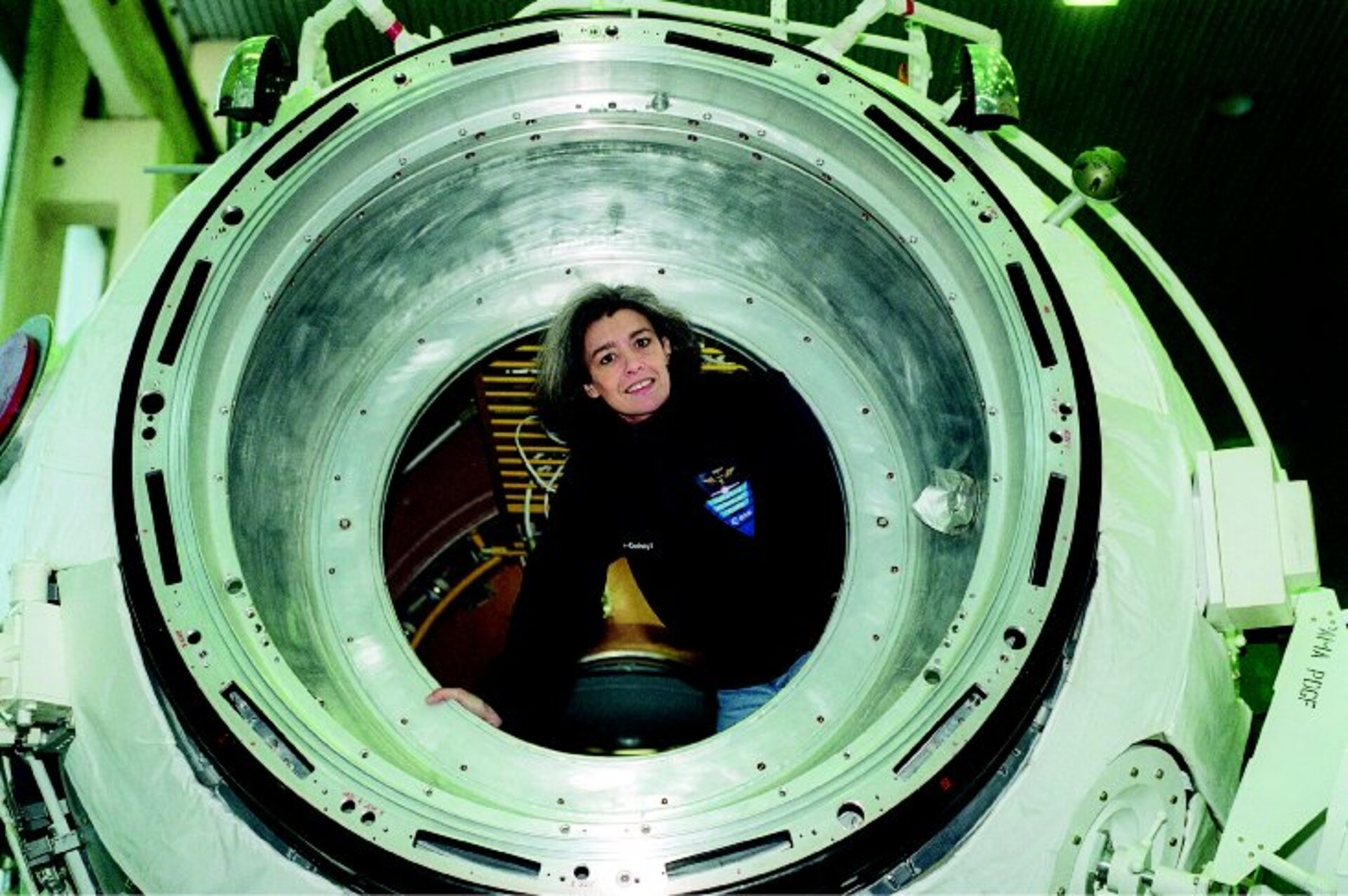

An interview with Claudie Haigneré

Currently training in Russia for the Andromeda space mission that will take her to the ISS in October, French 'spationaute' Claudie Haigneré (formerly André-Deshays) will be the second ESA astronaut to visit the station - and Europe's first woman.

Born in Le Creusot in 1957, just a few months before Sputnik 1 showed that the bounds of Earth's gravity could be broken, Claudie is currently the only woman among the sixteen members of the European Astronaut Corps. She is already a space veteran, with a space science mission – Cassiopee, in 1996 - behind her. We asked her the question she has had to answer about a million times:

How did you get started in the astronaut business?

"I was just 12 years old when Neil Armstrong became the first man to walk upon the Moon. For me, it was a kind of revelation. I was watching a dream turn into reality. A door was open. I didn't immediately imagine that it was open for me, but the lunar landing gave me a taste for space. I read a lot about the conquest of space, watched every documentary. But I chose to become a doctor - and I was working as a medical professional when my dream became possible.

In 1985, I was a hospital doctor. One day, there was a notice on the board from the French space agency CNES looking for scientists for their microgravity science programme. I had no doubts at all: I absolutely had to get an application form. I realised that my dream could be a reality, too. This was the door, and it was open. After that there was a long selection process; but I had a feeling I would make it all the way. In fact, only seven of us were chosen out of a thousand applicants.

Claudie is perhaps a little modest. When she saw that notice she was already well along a solid medical career. She specialised in rheumatology and sports trauma injuries, and was already developing an interest in aerospace medicine. The French space agency, and later ESA, were lucky to get her.

It is in the nature of an astronaut's career that you spend a long time between flights. So do you see yourself primarily as a scientist who has rare and exciting opportunities to work in orbit, or as an astronaut who does solid science to keep herself occupied between missions?

"As astronauts, our professional career is certainly marked by space flights, but in between flights we have a rich professional life, whether as engineers, scientists, experts in the development of ESA technical projects, or just as teachers. So we don't just hang around idly between flights. But I agree that we all wait impatiently for our first flight and from the moment we return we are already all thinking about the next. We know that we're very privileged people, which encourages us to be responsible and patient. We also know that impatience helps nothing. We want to fly. If we can't handle being patient, we know that there are plenty of others waiting to take our place."

You haven't really answered the question, Claudie. Are you a scientist or an astronaut?

"At present, after nine years of almost continuous training (I began as a crew back-up in 1992) I think of myself more as a professional astronaut who has acquired a specific expertise in space systems and microgravity science programmes.

It's hard to be a doctor when you have no patients, or a scientific researcher without a personal research programme and without enough time to stay in contact with the scientific community and to keep up with the publications. Still, all of us in the European Astronaut Corps have our own professional specialisations. For example, between two major training spells I spent a lot of time working on the Life Science payloads for Columbus and what we could do with them."

Your Andromeda mission will be an important step forward for Europe - including your native France. Is there anything you'd like to say to the millions of young Europeans who will be watching?

"Andromeda is important because it allows us to get the ISS orbital laboratories up and running. We can test out operational procedures years before Europe's Columbus module and the ATV are part of the station.

I think that we can also show young Europeans that Europe is a real space power, and an important partner in the ISS project. Europe has teams of engineers, scientists and astronauts whose competence is recognised by all our partners, especially the Americans and the Russians. Because of what we're doing up there, we hope that our young people will see that a career in science and technology can be fascinating and fulfilling. Like all young people, they will create their own future. But we can show them what that future might be.

They will be able to go much farther along the road we have opened: and don't forget, it's an adventure. All the same, it's a fine dream to want to be an astronaut. But it shouldn't become an obsession. A long time ago, William of Orange said:

"Point n'est besoin d'espérer pour entreprendre, ni de réussir pour persévérer"

"It is not necessary to hope in order to undertake an endeavour, nor to succeed in order to persevere."

At the moment, you are Europe's only woman astronaut. There are about 100 million young European women watching you. What would you say to them?

"I'd certainly like to see more women in the European Astronaut Corps. With just one out of 16, we are only 6% - which is very few compared with the numbers back in 1985, when the first astronaut selections were made. It seems to me that around 20% would be reasonable in the 21st century. Of course, we can't expect to reach equal numbers very soon - given the specific nature of the job, which demands total commitment and 100% availability - neither of which are easy for women of our generation. I am confident that the new generation will be in better shape to choose its own future without any constraints of inequality. It's certainly satisfying to do exactly what you want - but the price for it must not come too high. My own daughter Carla - she is three and a half years old - finds nothing strange in her mother's occupation. But then she spends a lot of time in a Russian kindergarten with other cosmonaut kids. In any case, if you ask her right now what she wants to be in the future, she'll tell you: "I want to stay a little girl."

But a woman in space, Claudie: are there special problems, special advantages?

"As for the physiology, short-duration flights have shown no major differences between the sexes. So far, very few women have made long-duration flights, so there is not enough data for accurate analysis. On the psychological level, though, there have been a number of studies on human behaviour in circumstances of isolation and confined living space. The evidence clearly shows that mixed crews perform best - in organising their work, in decision-taking, in conflict management and in their contacts with "ground control". Men and women are different but complementary. We must let them live and work together in their own ways, without trying to make them behave identically. When we explore the planets, it will be a huge step forward for the entire human race. And the human race has two sexes."