Flight Dynamics

No ESA satellite reaches its destination without the ‘spacecraft navigators’ – the flight dynamics experts who predict and determine trajectories, prepare orbit manoeuvres and determine satellite attitudes and pointing.

Flight dynamics experts at our ESOC operations centre work on every ESA mission, from those in Earth orbits, like Swarm and Biomass, to those exploring the depths of our Solar System, like BepiColombo or JUICE. They are involved from the first steps of a mission’s concept to the last command sent.

What we do

The experts work with data from ground tracking stations and from the spacecraft themselves to determine trajectories and orientations, feeding this information back to the spacecraft operations teams who ‘fly’ the missions.

Flight dynamics data are processed by a ‘team of teams’ – with separate groups dedicated to Earth-orbiting missions and deep-space missions. The split between them is conveniently set as ‘those this side of the Moon’ and the rest.

Access the video

Every satellite mission has strict requirements. For one of the Earth observation missions, for example, the flight dynamics experts ensure that the satellite flies through an imaginary tube with a diameter of only 120 m as it circles Earth at 7.45 km/s.

For a spacecraft destined to orbit a planet, such as Mercury or Jupiter, they must determine the right time, duration and direction to fire the engine to guarantee a successful arrival and all this after the spacecraft has travelled through our solar system for billions of km and several years.

To gain sufficient energy to reach their target destinations, many interplanetary spacecraft must perform gravity assist manoeuvres (also referred as ‘swing-by’ or ‘fly-bys’) at solar system bodies: planets and or moons of these planets. Such manoeuvres are tricky since an exact point in space must be reached to consider the gravity successful, and several previous small manoeuvres help reach the right point at the right time.

During the summer 2024, JUICE mission controllers at ESOC implemented the first-ever double gravity assist, passing first by the Moon, then by Earth. This highly risky concept allowed the mission to save even more fuel than a “standard” Earth gravity assist. It was invented, prepared and flown by ESOC teams, among which flight dynamics played a major role.

This demands highly precise, analytical work and every calculation is double-checked by an independent group to ensure correctness and accuracy.

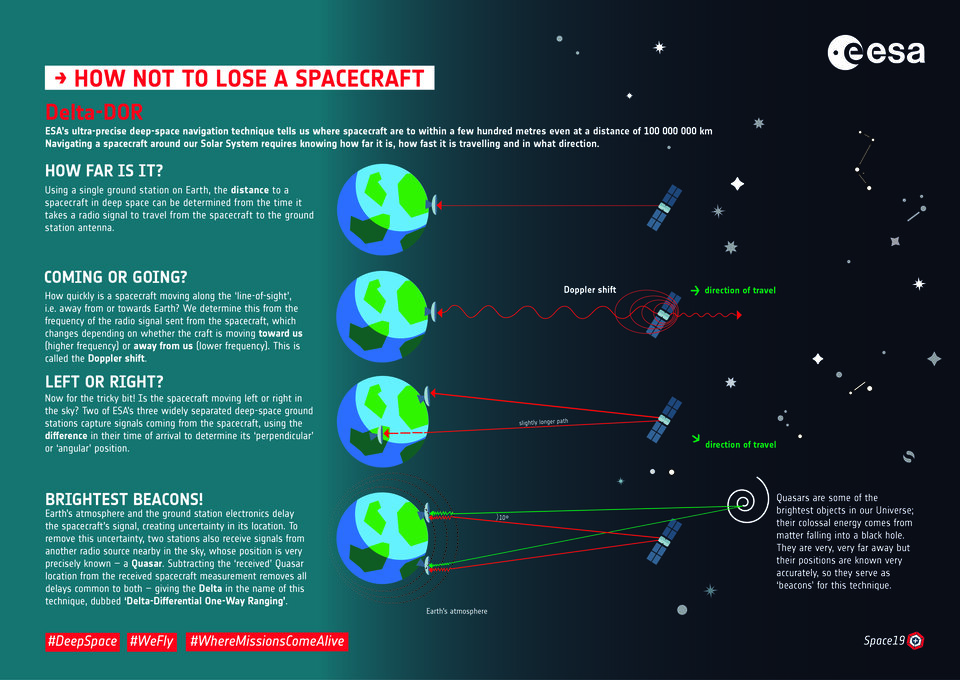

Telemetry or scientific data are not the only data received from the spacecraft. On the one side, calculating the time a signal takes to reach the spacecraft allows for a range measurement, while on the other side, measuring how the transmission frequency shifts, in what is called the ‘Doppler shift’, allows to calculate the spacecraft's radial velocity. Both data help mission operators navigate the spacecraft through the solar system with the utmost precision.

Telemetry or scientific data are not the only data received from the spacecraft. As the spacecraft journeys through space, its transmission frequency shifts in what we call a ‘Doppler shift’. Calculating this shift helps analysts navigate spacecrafts through the solar system, allowing them to determine their radial velocity and perform range measurements from the ground station.

One very accurate technique applied by the ESOC experts for interplanetary navigation uses special measurements called ‘delta DOR’ – for Delta Differential One-way Ranging.

Delta-DOR measurements from a pair of widely separated ground stations are combined with the measurements mentioned above to determine the position of a spacecraft as far away as 150 million kilometres – the mean distance from Earth to the Sun – to within less than 1 km. But these measurements can be applied at longer distance, JUICE at Jupiter being a good example.

Only a few of the world’s space agencies have perfected this highly precise technique. Using two orthogonal pairs of our ESTRACK stations (Cebreros-Malargüe and Cebreros-New Norcia) allows to reach this accuracy in all directions.

Case study

At some point in time, spacecraft also reach the end of their life. To avoid a further pollution of the space environment with space debris, satellites are not left in their science orbits, but are actively manoeuvred for re-entry or moved to ‘graveyard orbits’, where they do not pose a risk to other spacecraft.

In 2023, after exceeding its planned life in orbit, Aeolus was ending its life while getting ever closer to the Earth. Its fuel was almost spent. If left alone, it would have naturally fallen back within a few months.

A natural reentry means that the entry point cannot be controlled: the satellite can reenter anywhere, including inhabited areas. Heavy satellites must reenter over uninhabited areas, like the South Pacific. In the case of Aeolus, itwas never designed for a controlled reentry, neither in terms of fuel nor in terms of required thrust level.

ESA went above and beyond by attempting an assisted reentry – the first of its kind in history. Such a reentry does not guarantee a pinpoint location for the potential surviving fragments, but a vaster empty area along the ground track – the path on Earth right below the satellite’s trajectory.

ESOC flight dynamics teams played a major role in this attempt. They planned the series of manoeuvres and verified that the satellite would survive them until the final journey through the atmosphere.

On 28 July 2023 at 18:46 UTC, the potential surviving fragments of Aeolus may have reached the ground close the Atlantic Ocean and Antarctica thanks to the excellence of flight dynamics and the other teams involved (operations and space debris).