Bringing space science back to Earth:

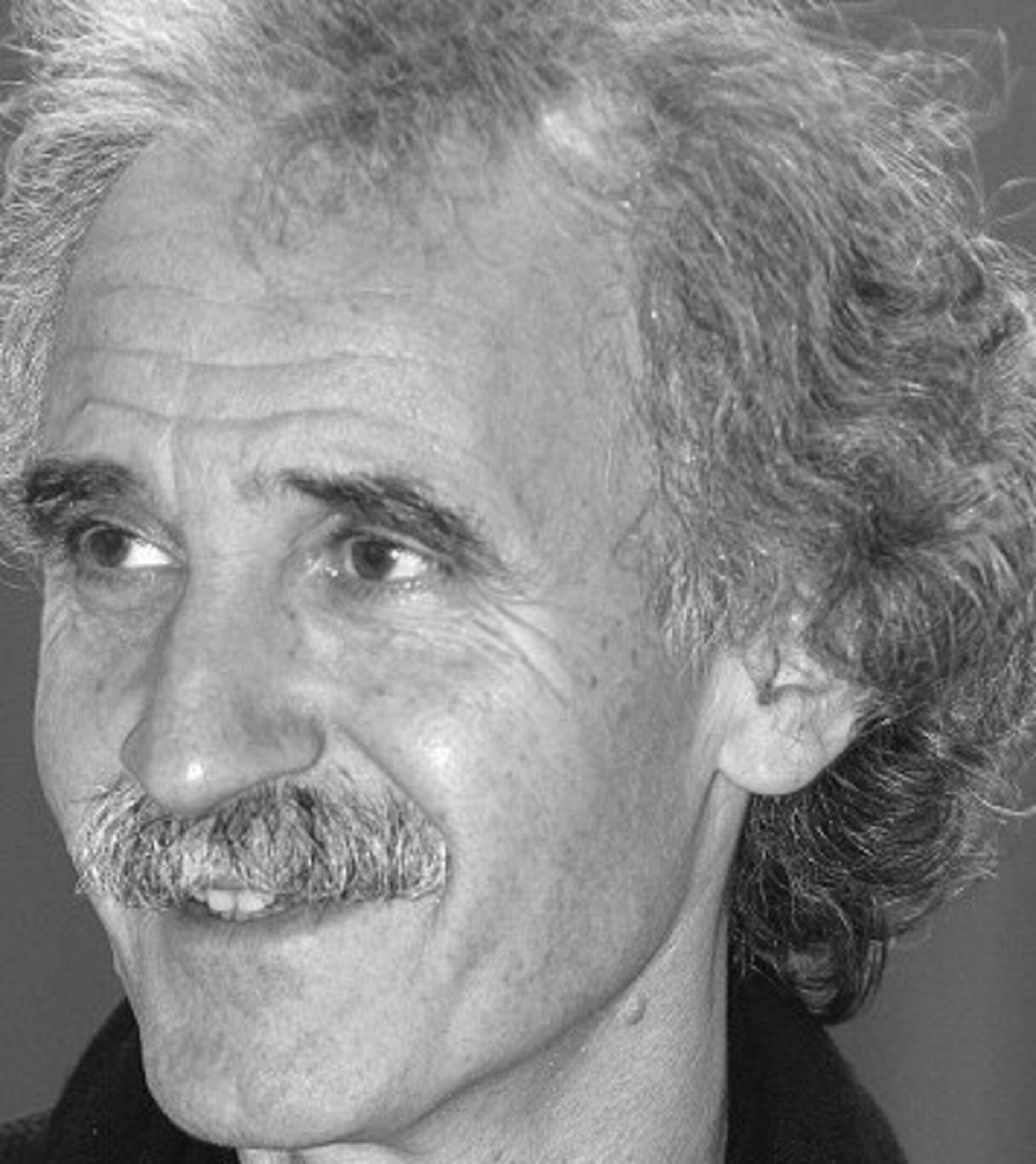

An interview with Jean-Pierre Bibring

Jean-Pierre Bibring is very conscious of how human activity on Earth can affect our environment and put human life at risk, and that space research can have a positive impact on our society. His OMEGA experiment on Mars Express will help answer basic questions about Mars, which could help us understand how our planet evolves too.

Jean-Pierre Bibring

Professor of Physics, University of Paris, Orsay, France, and Astrophysicist at IAS, Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale, Orsay

Principal Investigator, OMEGA, Mars Express

Born: 24 June, 1948 in Paris, France

Masters Degree in Physics and PhD in Astrophysics, University of Paris, Orsay, 1978. Since then Jean-Pierre has taught physics and astrophysics at all university levels, in addition to co-ordinating space research programmes.

His current responsibilities as well as his work on Mars Express include: Lead Scientist of the Rosetta Lander (ESA Rosetta mission); Principal Investigator of the CIVA investigations (panoramic and microscopic spectral imaging) on board the Rosetta Lander; and Co-Investigator of several other experiments on Solar System exploration missions, such as ESA's Venus Express, NASA/ESA Cassini/Huygens and NASA MRO.

Jean-Pierre is married with two daughters. His hobbies are predominantly organised around music, and he tries as much as possible to couple scientific and social activity.

We have a tremendous potential for making major discoveries: we have been waiting for this event for almost 15 years!

ESA: Here we are, close to arriving in Mars orbit, how do you feel?

Jean-Pierre Bibring

Both very anxious and excited. Anxious, since we faced the dramatic failure of the Mars '96 launch, followed by two losses of NASA Mars missions in 1998, demonstrating how risky the space adventure can be. On the other hand, the success of the Mars Express orbit insertion and its follow-on orbital operations have a tremendous potential for major discoveries: we have been waiting for this event for almost 15 years now!

Fascinated by early space achievements, and growing up at a time science and technology were still highlighted in our society, I went to Paris University.

ESA: What first inspired you to become interested in space, and how did you enter the field?

Jean-Pierre Bibring

Fascinated by early space achievements, and growing up at a time when science and technology were still highlighted in our society, I went to Paris University to learn physics, which appeared to me among the most appealing and promising disciplines.

I went into nuclear physics, at the time the first lunar samples were brought back to the Earth by the impressive Apollo and Luna programs. I thus joined the large and stimulating international lunar and extraterrestrial sample community, studying the lunar samples as unique 'detectors', having recorded the history of the Solar System over its entire history (through nuclear effects induced in the microscopic grains of the lunar regolith).

I entered space activity through laboratory studies of samples returned by space missions. We then proposed to CNES a first space investigation, designed to collect extraterrestrial (cometary) matter on board space stations, which was implemented on Salyut 7, then Mir. At the same time, I was invited to contribute to two investigations on board the Halley fly-by missions in 1986, the Soviet Vega probes and ESA's Giotto.

I then shifted towards activity entirely focused on space missions, one dealing with the search for the conditions prevailing at the time the Solar System formed (study of cometary matter, leading to responsibilities on the ESA Rosetta mission), and the other one with the study of differentiated bodies, with an emphasis on Mars (I was the Principal Investigator of the ISM infrared spectral imager on board the Soviet Phobos missions in 1989, then OMEGA on board Mars 92, 94 and 96, which led to Mars Express).

We are conducting a truly collective experience and this is fascinating.

ESA: What drives you in your job?

Jean-Pierre Bibring

I entered the Solar System space explorations thanks to a co-operation with the Soviet space programme, then the Russian one. With Mars Express, we continue these pioneering activities with the goal of contributing to a better understanding of what drives the evolution of the planets. This activity is shared with my colleagues at IAS, who demonstrate impressive skill, professionalism and enthusiasm in these investigations.

In addition, our experiments are largely co-operative, in France, Italy and Russia, with co-investigators from several other countries. My role can't be decoupled from that of the entire group. We are conducting a truly collective experience and this is a major driver.

ESA: What fascinates you about Mars in particular?

Jean-Pierre Bibring

Mars is unique in that it can help address key questions concerning the evolution of the Solar System, including the Earth. Why and how did the planets, with so similar initial conditions (age, location, material), evolve towards so different present states, as for the Earth to still harbour life?

Mars is large enough to have undergone all major steps of planetary evolution, including a phase of internal activity, as shown by a rich variety of tectonic, volcanic and fluvial surface structures.

On the other hand, Mars is small enough not to have erased the records of all this previous activity, so that you can still see the diversity of processes that contributed to the planetary evolution until its geological death. Mars has the potential to deliver clues to the impressive planetary diversity we see that comes from our first phase of exploration initiated in the 1960s.

This unique role in comparative planetology explains why Mars is the target of so many major space agencies over the next decades in such a rich programme of research.

Today's goal is to identify and explain the specifics of each planet. Has Mars ever hosted similar conditions to the Earth? Did life ever form on Mars, and can we identify sites in which extinct - or extanct - life forms could be found? Or conversely, could we demonstrate that the terrestrial conditions that enabled our biological evolution were highly specific, and unique, at least in the Solar System?

Studying Mars is thus not limited to understanding the evolution of this planet, but also contributing to an unprecedented view of the Solar System, with an emphasis also on our Earth.

Never before perhaps has space research played such an elevated social role, while offering tremendous scientific excitement.

ESA: What do you hope to find with your experiment, and why is that important?

Jean-Pierre Bibring

At present, most of our understanding of Mars surface structures and evolution comes from the interpretation of optical images and altimetry data, with still only a very limited amount of information on the composition of the rocks, soil and frosts.

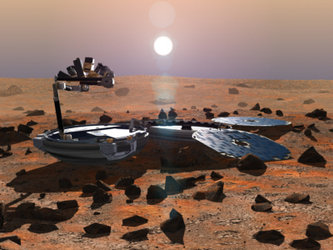

Our experiment, OMEGA, is designed to identify the composition of the surface and atmospheric components, on each resolved pixel of the images our instrument will acquire. So we should be able to build maps of abundances, of the entire surface with a resolution of a few kilometres and, for selected areas, a few hundred metres.

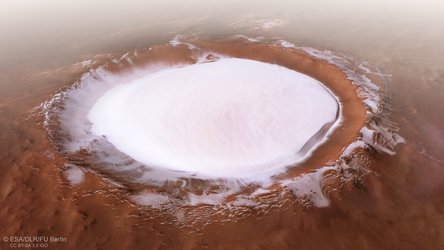

We expect to find most minerals, such as silicates, oxides, hydrated minerals and sedimentary rocks. In addition to minerals, we will map ice and and frosts, as a function of latitude, longitude and season, and identify their composition.

As for the atmosphere, we will be able to measure major and minor constituents on each pixel, and determine the composition of aerosols (ices and minerals) as a function of altitude. With these surface and atmospheric composition images, together with the other investigations on Mars Express, OMEGA should contribute significantly to our understanding of the evolution of the planet, from geological timescales to seasonal variations.

ESA: Do you have an example of something you are looking for?

Jean-Pierre Bibring

To illustrate the importance of a potential finding, let's take carbonates which, up to now, have not been definitely identified on Mars. The present atmosphere is very tenuous (it doesn’t filter the solar ultraviolet radiation and liquid water isn’t stable).

Although it is predominantly carbon dioxide, the total amount of carbon dioxide is considered to be much smaller than it was initially. Most of the it has disappeared from the atmosphere, as happened on Earth, where it mainly dissolved in the oceans and precipitated as carbonates. This is why you find large limestone structures near oceans. If liquid water ever existed on Mars, a similar process could have occurred.

Identifying carbonates would both indicate the existence and location of past oceans. This is critical since, in the present conditions, liquid water cannot exist on Mars given the low atmospheric pressure.

Should we demonstrate, through finding carbonates, that oceans existed on Mars, then that would open the possibility that they could have hosted the conditions for life to grow, as on Earth. These sites would be favoured targets for future missions, as they would be the most likely to contain microfossils if ever life once emerged on Mars.

ESA: If there's one thing you could say to someone wanting to enter the space field, what would it be?

Jean-Pierre Bibring

Astronomy and then astrophysics have always played a double role in society: satisfying human curiosity for understanding where we are, and serving the society as an applied science.

Nowadays, this double role has become even more important. On one hand, space exploration, in particular the unmanned interplanetary journeys, has revealed a totally unprecedented view of the history and geography of the Solar System, and in particular of our Earth.

On the other hand, this research is now not merely a matter of satisfying a basic curiosity. There is an urgent need to understand the subtle processes in action on the Earth now that, simultaneously, we have both the means to acquire a new vision of cosmic history, including the emergence and evolution of life, and the means to alter the environment on Earth which could potentially jeopardise human life.

Space activity has the potential to address very effectively the relevant issues, and to significantly contribute to solving them. Never before perhaps has space research played such an elevated social role, while offering tremendous scientific excitement.