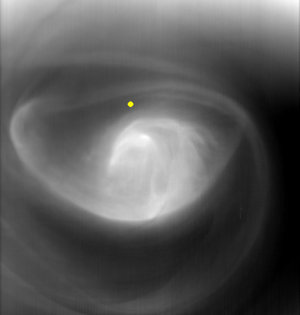

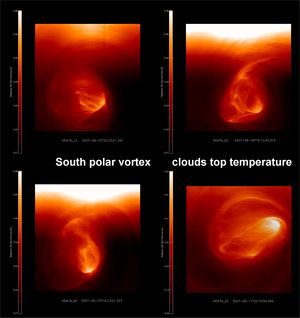

South polar dipole movie – different view

This video is composed of a set of images acquired by the Visible and Infrared Thermal Imaging Spectrometer (VIRTIS) on board ESA’s Venus Express, during two observations slots in August 2007. The spacecraft was watching Venus's south pole from around 65 000 km. The video was obtained at 3.8-micrometre wavelength, allowing the instrument to see the cloud-top thermal emission at an altitude of about 60–65 km. The swirling pattern is a polar vortex, also called a polar dipole.

Venus's atmosphere is the densest of all the terrestrial planets, and is composed almost entirely of carbon dioxide. The planet is also wrapped in a thick layer of cloud made mostly of sulphuric acid. This combination of greenhouse gas and perennial cloud layer led to an enormous greenhouse warming, leaving Venus’ surface extremely hot – just over 450 °C – and hidden from our eyes.

Although winds on the planet’s surface move very slowly, at a few kilometres per hour, the atmospheric density at this altitude is so great that they exert greater force than much faster winds would on Earth.

Winds at the 65 km-high cloud-tops, however, are a different story altogether. The higher-altitude winds whizz around at up to 400 km/h, some 60 times faster than the rotation of the planet itself. This causes some especially dynamic and fast-moving effects in the planet’s upper atmosphere, one of the most prominent being its ‘polar vortices’.

The polar vortices arise because there is more sunlight at lower latitudes. As gas at low latitudes heats it rises, and moves towards the poles, where cooler air sinks. The air converging on the pole accelerates sideways and spirals downwards, like water swirling around a plug hole.

In the centre of the polar vortex, sinking air pushes the clouds lower down by several kilometres, to altitudes where the atmospheric temperature is higher. The central ‘eye of the vortex’ can therefore be clearly seen by mapping thermal-infrared light, which shows the cloud-top temperature: the clouds at the core of the vortex are at a higher temperature, indicated by darker tones, than the surrounding region, and therefore stand out clearly in these images.

Venus Express has shown that the polar vortices of Venus are among the most variable in the Solar System. The observations shown in this video show how the south polar vortex changes shape over several hours.

The shape of this vortex core, which typically measures 2000–3000 km across, changes dramatically as it is buffeted by turbulent winds. It can resemble an ‘S’, a figure-of-eight, a spiral, an eye, and more, quickly morphing from one day to the next.