Looking after the 'heart' of the mission - Constantin Mavrocordatos, Payload Manager

As well as overseeing development of the SIRAL altimeter at the core of CryoSat's function, Constantin Mavrocordatos has also been responsible for developing an airborne version of the same sensor which will play a major role in validating results from the satellite once in orbit.

What is your role within the CryoSat team?

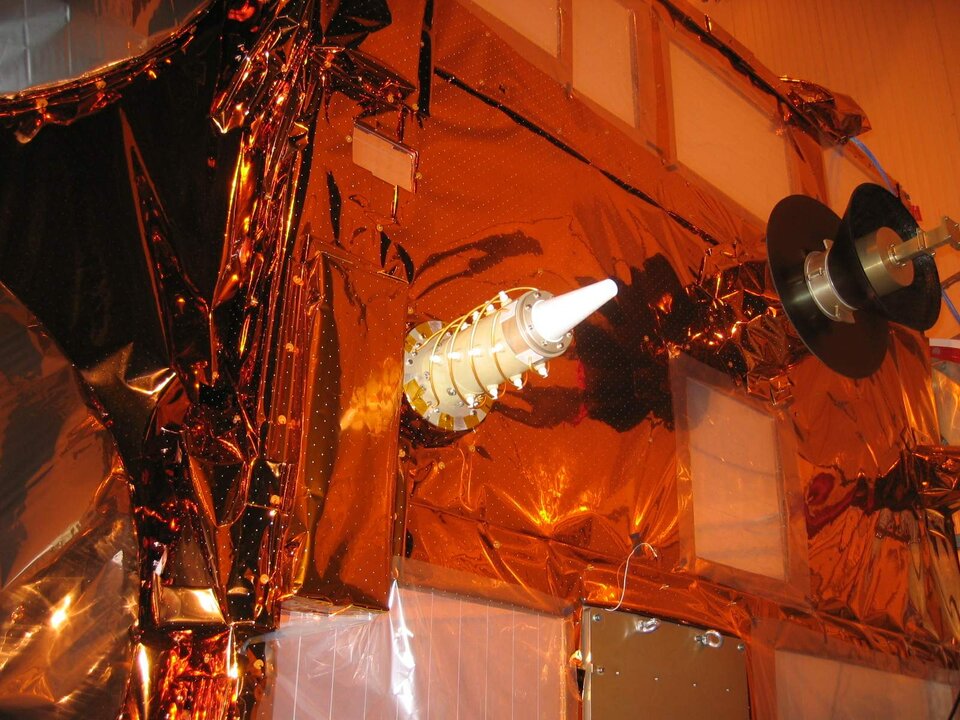

As Payload Manager, my role throughout the project has been to look after the 'heart' of the mission: its payload, and in particular the SAR Interferometric Radar Altimeter (SIRAL) and Doppler Orbit and Radio Positioning Integration by Satellite (DORIS) navigation receiver.

At the very beginning of the project, back in 2000, I was in charge of the definition of these instruments in such a way that industry could actually build them and meet our requirements.

Later, when the design and manufacturing of the different equipment started, my role has been to supervise the industrial activities, giving guidance, accepting or proposing alternative solutions to overcome problems, clarifying or focusing our needs and ultimately accepting the design and the performance of the instruments built.

For this, I was supported by a team of experts from ESA, but also from the French Space Agency CNES who developed and maintain the DORIS system. After launch, I will be involved in the commissioning activities, to make sure that the payload operates as expected and that its performance is stable.

In parallel to the spacecraft related tasks, I have been in charge of another activity inherited from my previous job in ESA: the development of an airborne version of the altimeter, called the Airborne Synthetic Aperture and Interferometric Radar Altimeter System (ASIRAS).

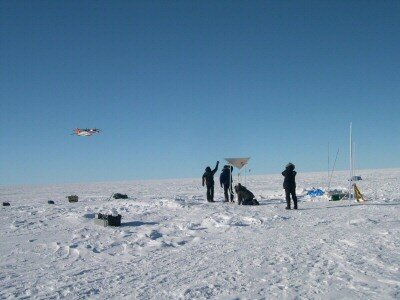

This instrument has been operational since March 2004 and is supporting the calibration and validation of CryoSat data, by collecting radar measurements over ice in a similar way as SIRAL will do from space.

ASIRAS will be used throughout the lifetime of CryoSat mission in the Polar Regions, simultaneously with the deployment of ground teams over the same areas. The comparison between CryoSat data, ASIRAS data and ground measurements will allow the identification and the correction of any residual measurement errors and thus contribute to the validation of CryoSat products.

Why is DORIS so important for SIRAL?

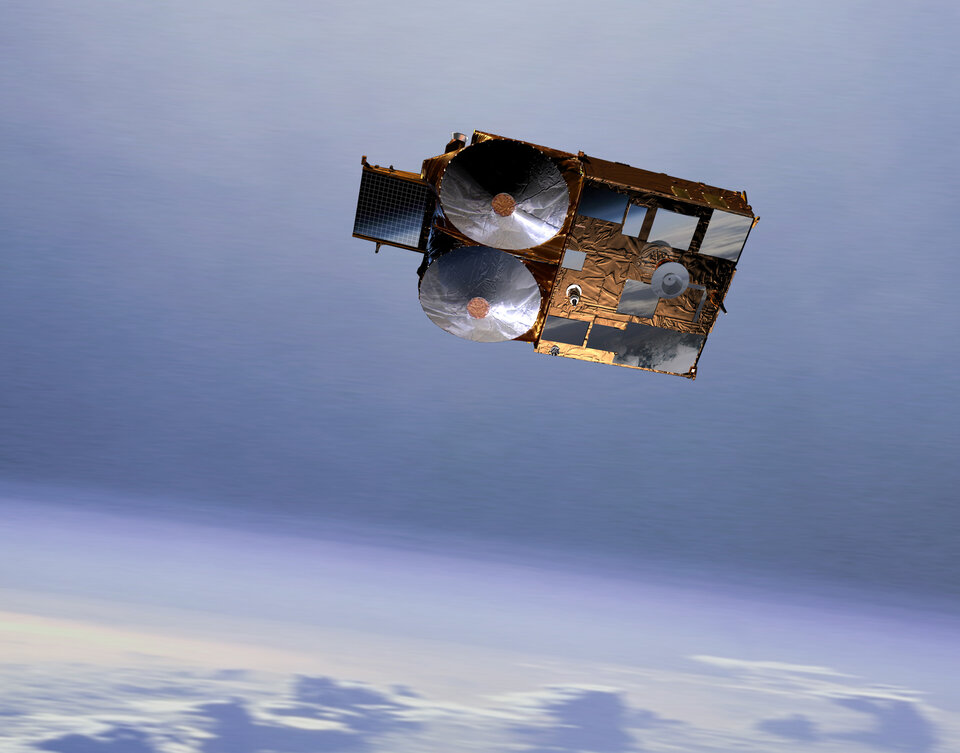

SIRAL measures the range between the satellite and a given point on the Earth surface. In order to convert this range measurement into surface height, it is necessary to know the position of the satellite when the measurement was taken. This is the purpose of DORIS.

After ground processing of DORIS data –ensured by CNES- the position of the satellite can be determined with an accuracy of only a few centimetres!

DORIS performs another role on CryoSat: it provides the position of the satellite in real-time, making it possible for the attitude and orbit control system to steer the spacecraft and keep the antennas pointed in the right direction along the orbit.

How did you become part of the project?

In fact, I was one of the very first engineers to join the project team after the selection and approval of CryoSat mission in 2000, after it was proposed by Duncan Wingham in late 1998.

When I joined the Agency's Technical Directorate in 1995, my first task was to develop new technology needed for future space-based radar missions and in particular for radar altimeter missions. I had then the idea to investigate a new altimeter concept, designed for height measurements over topographic surfaces such as ice or land.

The novelty of this particular instrument was the implementation of SAR/Interferometric capabilities on a classical radar altimeter, generally designed for observation of ocean surfaces.

In addition to the inherent range measurements of any radar altimeter, these new features make it possible to determine the direction of the reflected echoes captured by the radar and consequently derive the location of the measurements on the surface. The combination of the horizontal location of the measurement with the vertical measurement of the range, is the key to accurately measuring the surface height of topographic surfaces from space.

After internal investigations and presentations to different national space agencies, it became possible to further assess this concept through industrial studies initiated in 1997. The outcome of these studies, formed the basis of what later became the SIRAL instrument, and I naturally joined the team at the very beginning of the CryoSat programme.

What did you do before joining ESA?

I left Greece after secondary school and went to France for my subsequent studies. I graduated as an Electronics Engineer in Lyon and then moved to Toulouse, where I obtained a PhD in Electronics from Sup’Aéro (also called Ecole Nationale de l’Aéronautique et de l’Espace). During my PhD thesis, I designed and built a real-time SAR processor for an imaging airborne radar called 'VARAN-S', operated by CNES. This processor, delivered an onboard radar picture of the area over-flown by the aircraft, which was an antique B-17 used for scientific campaigns.

At that time –about 20 years ago- the computers were much too slow. The development of such a processor was then a real challenge. Only specialised computers could match the needs of this application by combining digital and analogue processing techniques.

In 1989, I joined Alcatel Espace in Toulouse and started working as system engineer on radar projects. I was then in charge of the Poseidon-2 altimeter (which is currently flying aboard the Jason-1 mission) until the middle of Phase B in 1995, when I moved to ESA.

What have you most enjoyed about working on CryoSat?

It has been very rewarding, and a rather unique experience, to be able to follow and to play a key role throughout the complete space mission. Usually, the normal duration for a space mission, from concept level to launch, spans well over a decade.

In addition, the responsibility for the mission changes hands during its life within an organisation like ESA: new concepts and new ideas are generally incompatible with the constraints of the development phase, where the costs and the schedule are a significant driver. This makes it difficult typically for an engineer to be involved in all phases.

Another important feature of this project is the small size of the core team. The result is a higher level of responsibility and an enhanced knowledge and understanding of all aspects of the mission by each member of the team. This increases our motivation and team spirit and makes everyday work a pleasure. Of course the drawback is a workload that is very high and sometimes implies sacrificing personal and family time. However, I judge the result to be very positive overall!