El Niño

In Spanish El Niño means 'the Christ Child' – a name give to it by the Peruvian fishermen who hundreds of years ago noticed how sometimes their coastal waters grew unusually warm and fish grew scarce around Christmas time.

They had no way of knowing they were naming a vast weather pattern whose effects strike much of the globe.

Global damage

El Niño is an irregular oscillation in tropical Pacific currents, with wide-ranging consequences. These might include vastly increased rainfall in South America, drought in Australia and fires across southeast Asia, dying coral reefs in India, severe winter storms in California, a heat wave in Canada and intense hurricanes raging along the Pacific Ocean.

This phenomenon seems to occur every three to seven years. The last full El Niño took place in 1997-98 and is estimated to have caused more than €30 000 million of global property damage. This is why it is important to learn more about this event.

El Niño begins when a mass of warmer water from the western Pacific moves east, eventually displacing cooler nutrient-rich waters around the South American coast. This warmer water adds extra moisture to the atmosphere, raises rainfall levels and disrupts atmospheric circulation across the globe.

Tracking El Niño events

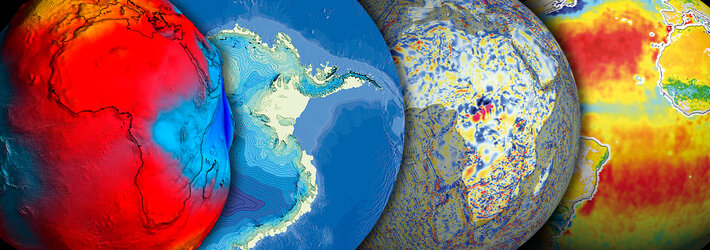

Space-based monitoring enables researchers to detect and track an El Niño event throughout its course.

Envisat's RA-2 Radar Altimeter was set to detect the 'bulge' of the sea surface caused by the warmer water when El Niño is still in the west and centre of the Pacific Ocean, an effect known as the Kelvin wave.

Once El Niño reaches the eastern areas of the Pacific then other instruments such as Envisat's Advanced Along Track Scanning Radiometer (AATSR) are designed to trace the surface water which as it is now 5º C warmer than the ocean around it forms an enormous ocean plateau up to 50 cm higher than the cooler water surrounding it.

Finally, as El Niňo arrives off the coast of South America, an ocean colour sensor such as the Medium Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MERIS) can monitor the changes in ocean colour as the phytoplankton decrease due to the loss of nutrient-rich cooler water. During this process, atmospheric instruments can closely follow the subsequent disturbances in air circulation and weather patterns.

Each week Earth observation adds a new frame to the ongoing film being shot of the Pacific Ocean. This continuous monitoring gives early warning of El Niño and also supplies climatologists with the data they need to understand more about how and why this phenomenon occurs and perhaps, tell us whether such occurrences are on the increase due to global warming.