A try-out mission for space debris clean-up?

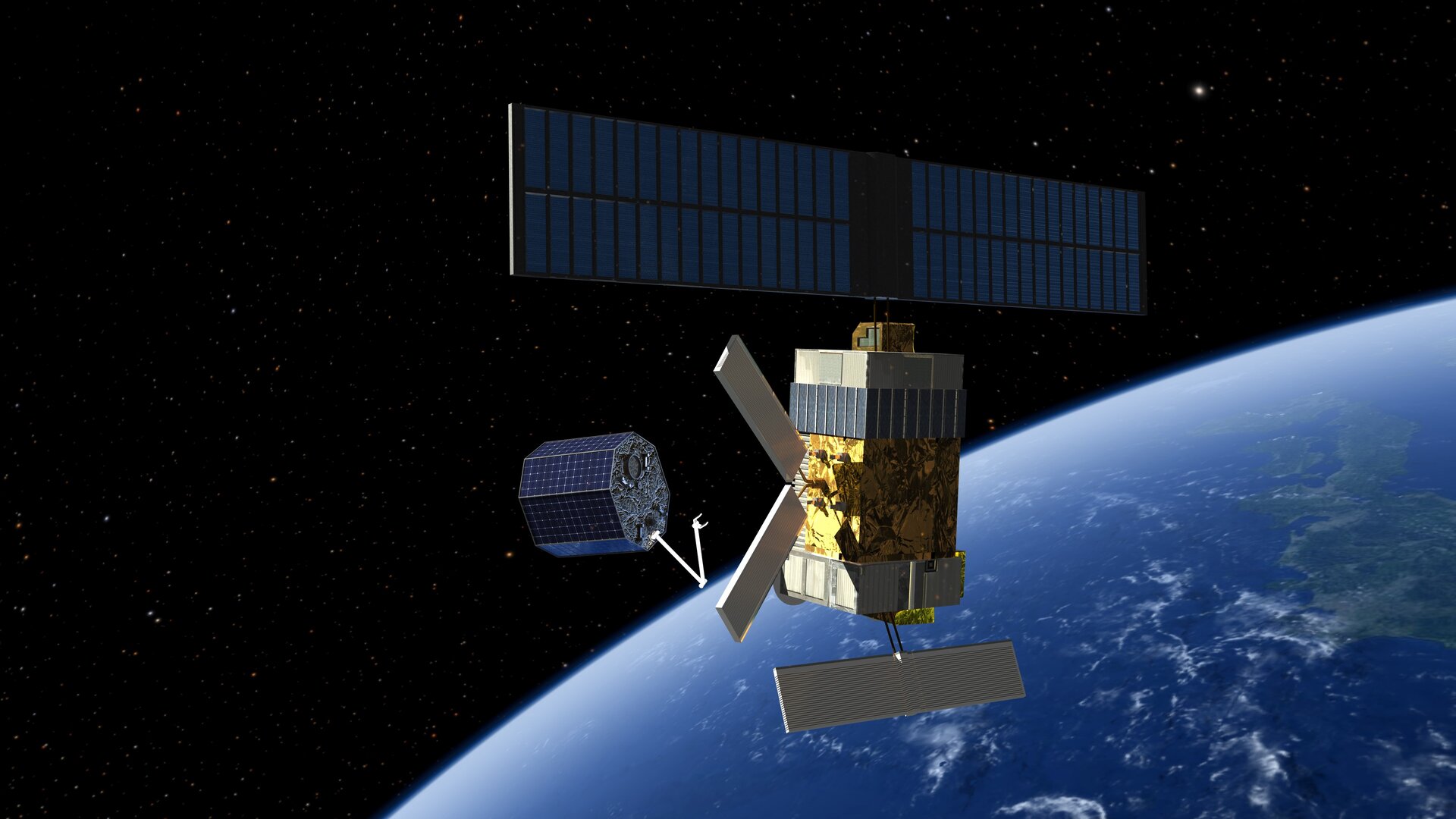

It takes a space mission to catch a space mission – so runs the theory behind ESA’s Active Debris Removal project, aimed at retrieving inert satellites from Earth orbit to reduce debris levels. But will a test mission be needed first to prove the many new technologies and concepts required?

In an unusual move for ESA, the Agency’s Clean Space initiative – addressing environmental protection for both Earth and space – staged a debate on the subject, part of the groundwork for a proposed Active Debris Removal mission, called e.Deorbit.

“The debate was the idea of Clean Space manager Luisa Innocenti, seeking a more definitive answer to the question of whether a predecessor mission for e.Deorbit is essential,” explained Jessica Delaval of Clean Space.

“It was staged like an actual debate at ESA’s Concurrent Design Facility at the ESTEC technical centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands. We had two teams putting forward the different views speaking before an audience, overseen by a chairman.

“It turned out to be a very educational and enjoyable way to cover the various issues involved.”

To IOD or not to IOD, that is the question

Around 5000 space launches since 1957 have led to an orbiting population of more than 22 000 trackable objects larger than a coffee cup. Only about 1100 of these are working satellites – the other 95% are space debris.

Leftover fuel or batteries inside old satellites can be driven to explode by remorseless orbital sunlight, spawning debris clouds. The only sure way to stop debris levels climbing is to remove complete satellites or related items such as launcher stages before they fragment.

Setting a satellite to capture another, uncooperative satellite is a formidable technical and operation challenge, however, in terms of automating guidance, navigation and control, devising a reliable capture method and coming up with a safe method of guiding the conjoined satellites back into Earth’s atmosphere to meet their fiery end.

The question is whether this shopping list of innovation is sufficiently difficult that an initial, smaller ‘in-orbit demonstration’ (IOD) mission is required first.

Examples of IOD missions include ESA’s 2009-launched Proba-2 minisatellite – demonstrating imaging technologies for the future Solar Orbiter mission – and the coming LISA Pathfinder satellite, flight-testing a suite of systems for a proposed gravitational-wave detection mission.

A team involved with ESA’s Proba family of missions spoke in favour of an IOD, with another represented by the CDF’s eDeorbit study team and system engineer opposed. The debate was chaired by Jack Bosma, the recently retired ESA Inspector General, attended by a mixed audience ranging from young graduate trainees to technical section heads.

Technology versus time

The arguments for centred around the fact that so much of the necessary technology for e.Deorbit is new and untested, from the guidance algorithms and sensors needed to catch a tumbling body to the uncertain method of capture to be used: would a net or grappling arms be preferable? How about a harpoon or contactless ion beam?

The prospect of failure is high enough that an IOD is the logical and safest way to proceed, the Proba team argued. An IOD would also allow the complex systems and operations processes involved in realising the e.Deorbit mission before they would have to see action ‘for real’.

The argument against came down to the high cost of a preliminary IOD mission: not just in terms of budget but actually time. By delaying the actual e.Deorbit mission from performing its duty – removing a dead satellite from a very busy orbit, where it runs the constant risk of being hit by other debris and spawning a new debris cloud – an IOD end up making a bad problem worse.

The audience had a wide variety of questions to put to both teams during what turned out to be a very lively debate, with the chairman drawing on his many years of engineering experience and knowledge of ESA management.

The outcome? A draw was the general opinion. The audience came out best, receiving one of the best insights into the pros and cons of in-orbit demonstrators they are likely to get.