What is gravity?

We understand that gravity is fundamentally a purely attractive force – it can only pull, never push – and that it is generated by any object with mass. But humankind has been trying to find a better answer to the question 'what is gravity?' for hundreds of years.

Italian Galileo Galilei was one of the first scientists to investigate the way objects are caused to move, around the turn of the 17th century. However, it was not until Isaac Newton started seriously investigating gravity later that century, that we really began to understand this feature of the Universe.

In 1687, Newton published his Universal Law of Gravitation. It provided mathematical expressions that would precisely describe the way objects moved in a gravitational field.

Not only did the expressions work for objects falling to the ground on Earth, they also explained how the planets moved through the night sky.

Unsurprisingly, this is heralded as one of the greatest works of science. There was only one observation his work could not explain: Mercury’s elliptical orbit gradually moves around the Sun, a phenomenon known as ‘precession’.

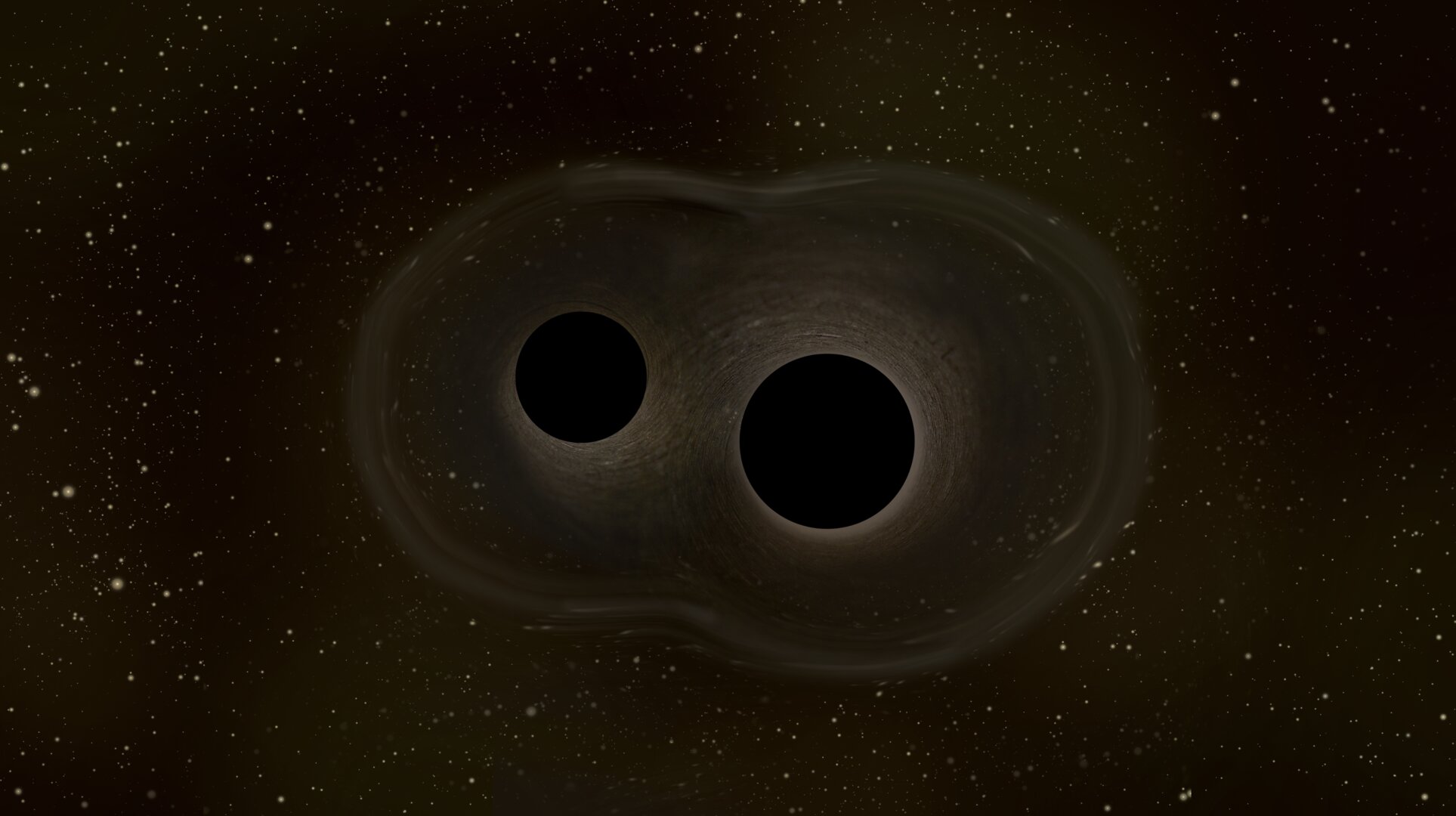

In the early 20th century, Albert Einstein developed his theory of general relativity in which he described gravity as a deformation in space, caused by the presence of massive objects, similar to the way a heavy ball would warp a sheet of rubber.

This deformation ‘tells’ smaller things how to move through space, so they either go into orbit or fell onto the larger celestial object.

This was a very different way to visualise space. In the past, it had been thought space was filled with a fluid known as ether. When no one could prove the existence of the ether, people began to think of space as simply empty. So, Einstein’s idea that space was like a fabric stretched across the Universe was revolutionary. He called it the ‘spacetime continuum’.

General relativity not only explained the precession of Mercury, it made a number of surprising predictions that, over the subsequent decades, have been observed to be true.

Among them was that light passing by a massive object would be deflected from its original path and that light escaping from a gravitational field would lose energy.

(In fact, satellite-based navigation systems such as GPS have to take this second effect into account, in order to pinpoint the location of their users precisely.)

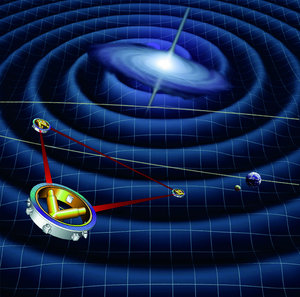

The latest prediction of general relativity to be tested is that certain celestial objects and events emit gravitational waves, which ripple through the fabric of space. Gravitational waves were directly detected for the first time by the advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in 2015, and the discovery was announced on 11 February 2016.

The next step is to detect them from space. To this end, ESA is building the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), the first space-based observatory dedicated to studying gravitational waves. ESA's LISA Pathfinder mission paved the way for LISA by demonstrating the key technologies needed for such an observatory.

Our understanding of gravity is still improving, and ESA's Euclid mission is also helping us answer the question of whether our understanding is complete. Euclid is studying how the Universe has evolved over the past 10 billion years to reveal how it has expanded and how structure has formed over cosmic history; from this, astronomers can infer the properties of dark energy, dark matter and gravity.