Building on Giotto and Rosetta

Comet Interceptor follows in the footsteps of earlier comet missions, including the ESA missions Giotto and Rosetta, which revolutionised cometary science. Giotto provided the first good resolution images of a comet’s nucleus, while Rosetta was the first mission to monitor the changing activity of a cometary nucleus before and after flying by the Sun.

For an overview of all previous and planned missions to comets, click here.

Giotto: the first close encounter with a comet

Launched on 2 July 1985, Giotto was ESA's first deep space mission. It was part of an ambitious international fleet of five space probes — two Soviet, two Japanese and one European — which aimed to solve the mysteries surrounding Comet Halley. In the week before Giotto reached the comet, the Japanese spacecraft made long-distance measurements while the Soviet spacecraft got to within 9000 km of the comet’s nucleus. The information they sent back allowed Giotto to home in with great accuracy on Halley's solid heart.

On 13 March 1986, Giotto flew within 600 km of Comet Halley’s nucleus, taking images along the way. It showed that Halley is roughly potato-shaped, its dark surface spotted with active regions shooting bright jets of gas and dust into space.

Years later, on 10 July 1992, Giotto became the first spacecraft to visit a second comet. It passed within just 200 km of Comet Grigg–Skjellerup. This provided a unique opportunity to compare the size, composition and velocity of dust particles coming from the two comets. Giotto also studied the interaction between the comet, the stream of particles in the solar wind and the magnetic field of the Sun and the planets.

Rosetta: two years tailing a comet

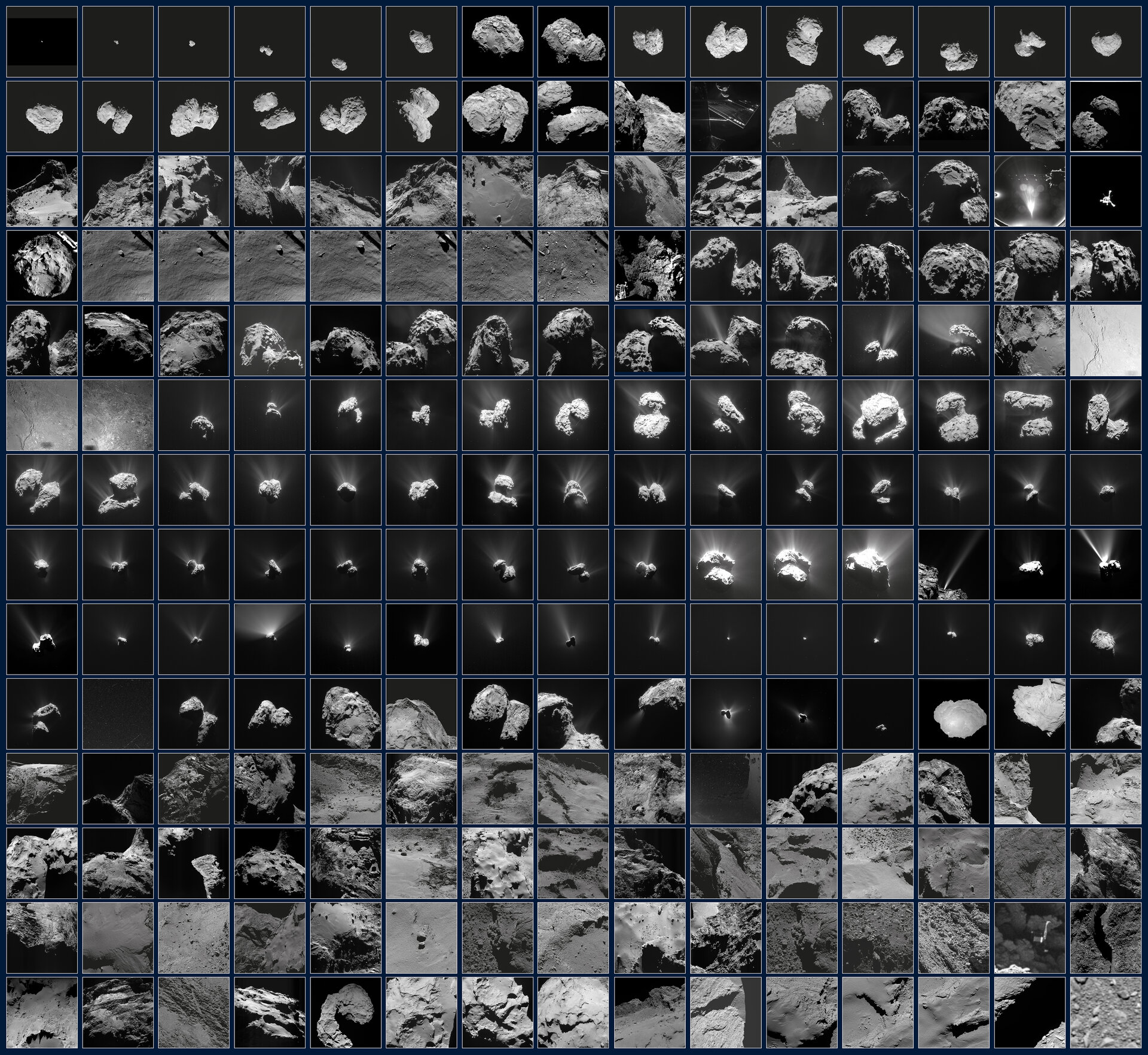

ESA’s Rosetta was launched on 2 March 2004. It reached Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko on 6 August 2014 and then flew alongside it for two whole years. Aside from taking images of the comet’s surface from different distances and from all angles, Rosetta showed for the first time how a comet is transformed by passing close to the Sun along its elliptical orbit.

Access the video

The high-resolution images that Rosetta took showed that as the spacecraft passed by the Sun, boulders moved around on the surface, fractures appeared, cliffs collapsed, new regions of ice became exposed, dust was blown away and sometimes fell back down. Interestingly, the colour of the surface changed from redder to bluer and back again during the time that Rosetta tracked it.

In another first, Rosetta carried a lander called Philae, which touched down (after bouncing) on the comet nucleus. The imprints that Philae left behind gave invaluable insight into how dense the surface is and what it is made of. It was found to be extremely soft — fluffier than froth on a cappuccino!

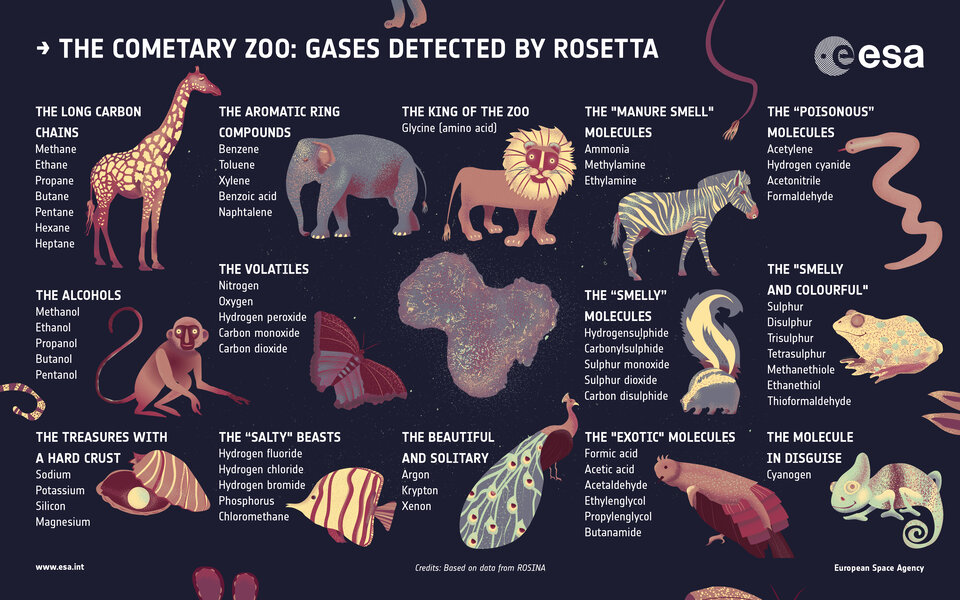

Rosetta also studied the ‘cometary zoo’ of gases coming off the comet. This includes many organic compounds that are important for life, as well as noble gases much like those in Earth’s atmosphere. On the other hand, the ‘flavour’ of water on the comet is different from that on Earth, leaving the role of comets in bringing water to Earth in doubt.

Comet Interceptor: 3D-mapping a new type of comet

One key question still unanswered after Rosetta is what properties were set in stone when the comet formed, and what features came later. Another puzzle is what exactly drives activity in comets. Comet Interceptor will address these questions by approaching a much more pristine type of comet and taking measurements from multiple locations at the same time.

Importantly, this mission hopes to snare a long-period comet or interstellar object that has never (or rarely) passed close to the Sun before. This is the first time such an object will be seen up close. All comets visited so far, including by Giotto and Rosetta, were short-period comets that frequently pass through the inner Solar System.

When reaching its target, Comet Interceptor will release two probes. The main spacecraft will pass around 1000 km from the comet’s surface, while the probes will get even closer, each taking a different route through the coma (the cloud of dust and gas surrounding the comet nucleus). In this way, it will map gas, dust and plasma in three dimensions. This was not possible with previous missions which sampled only a single location at a time.

Comet Interceptor will only fly past its target comet once, so unlike Rosetta it will not be able to monitor changes in activity over long periods of time. However, by combining detailed simultaneous observations of the nucleus and the coma, the new data can reveal how the features and activity on the comet’s surface are linked to the structure of its coma.

Click here to read more about the questions Comet Interceptor will help answer.