Theft of a million stars

Using ESO's Very Large Telescope, a team of Italian astronomers reveal the troubled past of the stellar cluster Messier 12 – our Milky Way galaxy ‘stole’ close to one million low-mass stars from it.

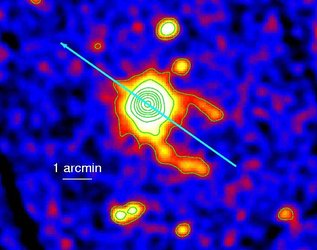

Globular clusters move in extended elliptical orbits that periodically take them through the densely populated regions of our galaxy, and then high above and below the plane (the 'halo').

When venturing too close to the innermost dense regions of our galaxy, (the 'bulge'), a globular cluster can be perturbed and its smallest stars ripped away.

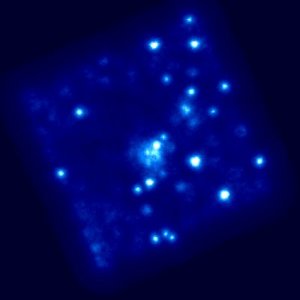

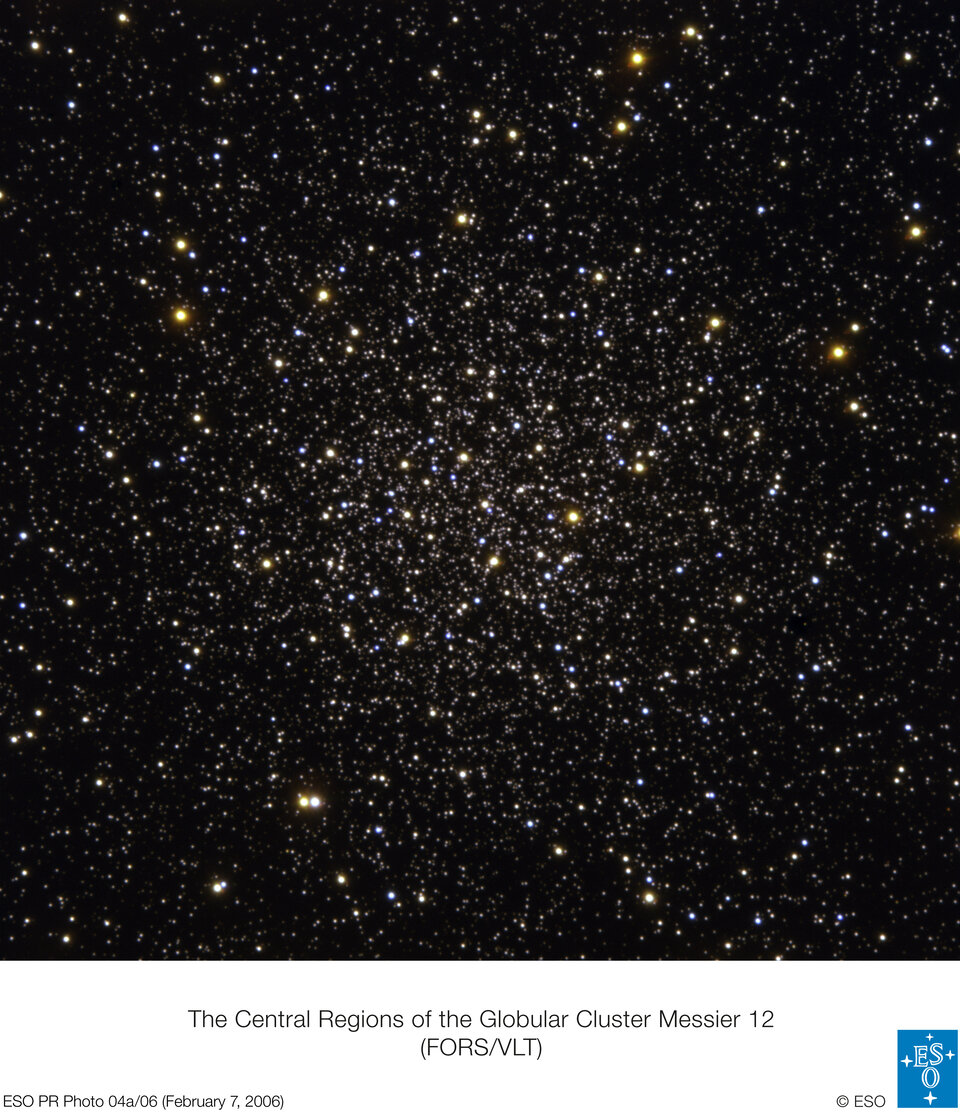

The astronomers, led by Guido De Marchi of the European Space Agency, measured the brightness and colours of more than 16 000 stars within the Messier 12 cluster with one of the Unit Telescopes of ESO's VLT at Cerro Paranal in Chile. The team could study stars that are 50 million times fainter than those seen with the unaided eye.

"In the solar neighbourhood and in most stellar clusters, the least massive stars are by far the most common. But our observations with the VLT show this is not the case for Messier 12," said De Marchi.

"It is however clear that Messier 12 is surprisingly devoid of low-mass stars. For each solar-like star, we would expect roughly four times as many stars with half that mass. Our VLT observations only show an equal number of stars of different masses."

The team estimated that Messier 12 lost four times as many stars as it still has. That is, roughly one million stars must have been ejected into the halo of the Milky Way, probably because it ventures too close to the galactic centre during its orbit.

"Our result is at odds with previous estimates of the cluster orbit, made over a decade ago, but is perfectly in line with a new analysis based on the Hipparcos reference data. In other words, Hipparcos data and our result go hand-in-hand to show that previous models of the cluster orbit were inaccurate," said De Marchi.

The total remaining lifetime of Messier 12 is predicted to be about 4500 million years, or about a third of its present age. This is very short compared to the typical expected globular cluster's lifetime, which is about 20 000 million years.

In 1999, the same team found another example of a globular cluster that lost a large fraction of its original content. They hope to discover and study many more clusters like these, since catching clusters while being disrupted should clarify the dynamics of the process that shaped the halo of our home galaxy, the Milky Way.

“This can tell us how globular clusters interact with the Milky Way and how they have ‘replenished’ the galactic halo with old stars over millions of years. But if we want to know exactly how these clusters orbit the Galaxy and what the galactic halo really looks like, we must wait for ESA’s 3D mapping mission Gaia,” said De Marchi.

Notes to editors:

The observations were using the by FORS1 multi-mode instrument attached to one of the Unit Telescopes of ESO's VLT at Cerro Paranal, Chile. The team of astronomers also included Luigi Pulone and Francesco Paresce of INAF, Italy.

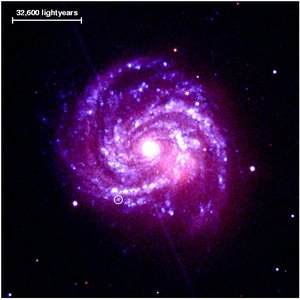

Messier 12 is one of about 200 globular clusters known in our galaxy. These are large groupings of 10 000 to more than a million stars that were formed together in the early stages of the Milky Way, about 12 000 to 13 000 million years ago.

Located 23 000 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus, Messier 12 is also known to astronomers as NGC 6218 and contains about 200 000 stars, most of them having a mass between 20 and 80 percent of the mass of our Sun.

Messier 12 got its name by being the 12th entry in the catalogue of nebulous objects compiled in 1774 by French astronomer and comet chaser Charles Messier.

Globular clusters are a key tool for astronomers, because all the stars in a globular cluster share a common history. They were all born together, at the same time and place, and only differ from one another in their mass.

By accurately measuring the brightness of the stars, astronomers can determine their relative sizes and stage of evolution precisely. Globular clusters are thus very helpful for testing theories of how stars evolve.

ESA's Hipparcos mission exceded all expectations and catalogued more than 100 000 stars to very high precision, and more than 1 million to lesser precision.

Hipparcos was so sensitive that, had it been positioned on Earth, it could have detected the 1 millimetre growth of a single human hair at a distance of 1 kilometre. The mission produced 16 volumes of data.

The successor mission to Hipparcos, Gaia, was approved in 2000 as an ESA Cornerstone mission to be launched around 2011. Gaia is a global space astrometry mission. Its goal is to make the largest, most precise map of our Galaxy by surveying an unprecedented number of stars - more than a thousand million.

For more information:

Guido De Marchi, ESA ESTEC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands

Tel: +31 71 565 8332

E-mail: gdemarchi @ rssd.esa.int