Life on exoplanets?

The question ‘Are we alone in the Universe?’ has been asked by humankind for centuries. The field of astrobiology seeks to answer this question. By studying the origin, evolution and distribution of life in the Universe, astrobiologists hope to better understand the nature of life and whether it could exist on planets other than Earth.

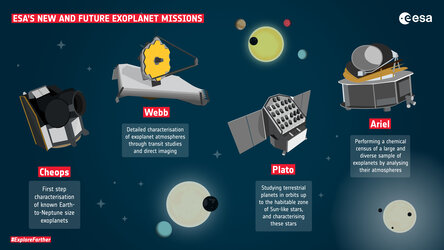

Missions such as the European Space Agency’s Cheops (Characterising ExOPlanet Satellite), the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope and the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope (Webb) as well as ESA’s upcoming Plato (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars) and Ariel (Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey) can pave the way for future astrobiology research by allowing scientists to study exoplanets and identify which types of planets outside the Solar System could be suitable for life.

Choosing the right exoplanet

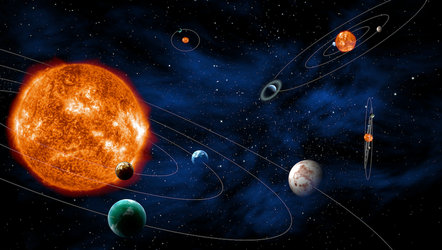

To find potentially habitable exoplanets, scientists must think about what makes a planet suitable for life. With around 6000 confirmed exoplanets, they must make choices about which ones to focus on.

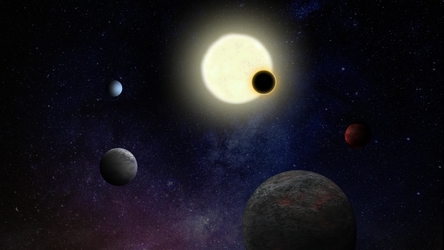

Although we do not know exactly what makes a planet liveable, one strategy is to look for exoplanets orbiting within the habitable zone of their star – the region where the energy from the star and the greenhouse effect from the planet’s atmosphere could be just right for liquid water to exist. Liquid water is key because, based on our current study of living beings on Earth, it is a requirement for life as we know it (more on this later).

An exoplanet’s potential habitability is also influenced by the light and energy a star gives off. The habitable zone of a small, cool red dwarf star such as TRAPPIST-1 lies much closer to its star than the habitable zone around our Sun. Red dwarf stars also stay active for much longer than stars like our Sun. Because of this, an exoplanet orbiting in the habitable zone of a red dwarf star is exposed to far more outbursts of stellar activity than Earth. This means that even if liquid water exists on the surface, effects such as stellar flares might still make these planets hostile to life.

An exoplanet zoo

In the hunt for potentially habitable exoplanets, searching for planets similar to Earth is an obvious choice; however, our study of exoplanets so far reveals that they come in many shapes and sizes. Many of the exoplanets we have detected are unlike anything we have in our Solar System, but we often describe them by comparing their size or mass to the familiar planets. This is where terms such as ‘super-Earth’ or ‘mini-Neptune’ come from.

With such a wide variety of worlds in the Universe, scientists must also consider whether exoplanets that look totally different to those that exist in our Solar System could be suitable for life. So far, no exoplanets are known to host life. Researchers have theorised about the possible habitability of water-covered exoplanets or mini-Neptunes with thick atmospheres, but more research is needed to understand such exoplanets and determine their suitability for life. ESA’s current and future missions help characterise different types of exoplanets.

Looking from a distance

Our nearest exoplanet neighbour is four light-years away. Travelling on a commercial jet, it would take approximately five million years to get there. This means that instead of using direct methods – such as looking for microbial life in a drop of pond water – we must use indirect methods to assess their potential for harbouring life.

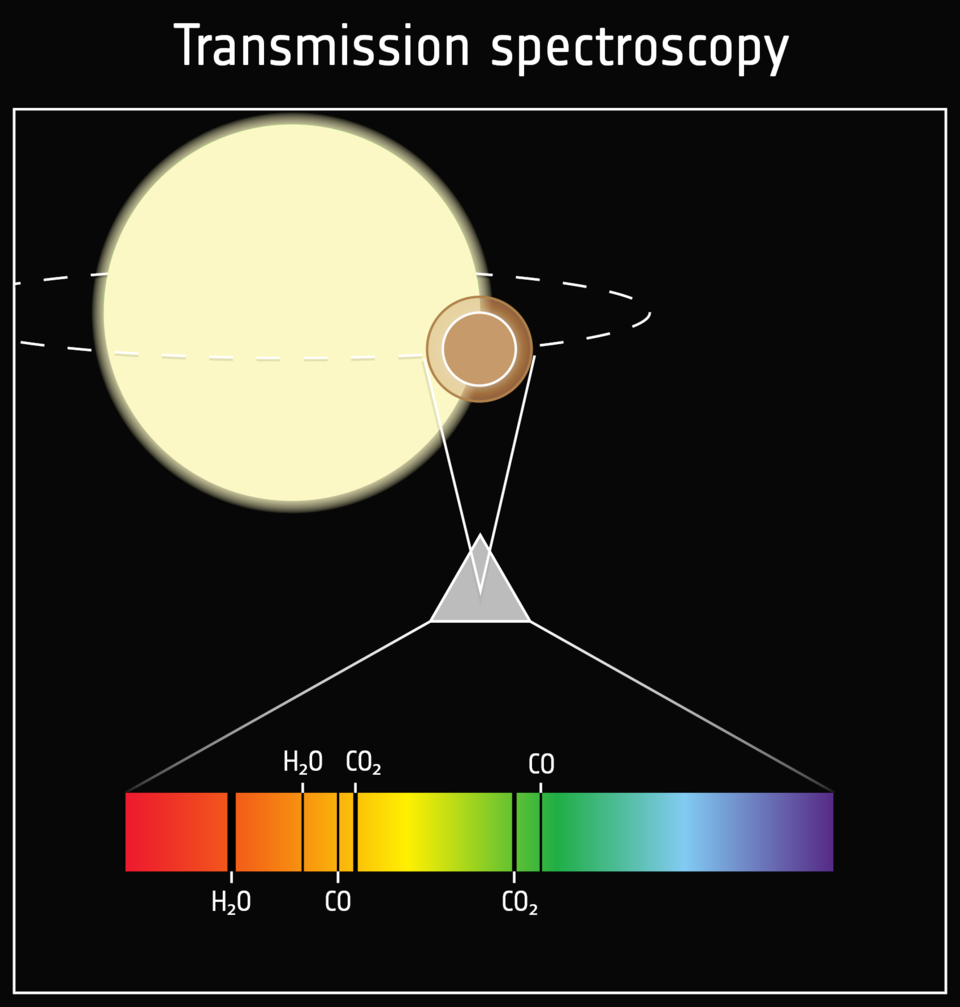

One method Webb, Hubble, and in future Ariel, can use to analyse exoplanet atmospheres is called transmission spectroscopy. With this technique, the telescopes look at light from a star that has passed through the atmosphere of an exoplanet. Molecules in the exoplanet’s atmosphere absorb some of this light, leaving a ‘fingerprint’ in the spectra. Scientists read the spectra from the telescopes to deduce which molecules are present in the exoplanet’s atmosphere.

However, reading a spectrum is not as simple as it sounds. Often, the ‘fingerprints’ of different molecules overlap, much like the fingerprints on a glass that has been touched by many people, making it difficult to decipher which molecules are present.

Spectra sleuths

When scientists analyse spectra from exoplanet atmospheres, they can look for molecules and patterns that indicate habitable conditions or even molecules and patterns that could plausibly be produced by life – known as biosignatures.

Interpreting potential biosignatures is context dependent. There are many types of exoplanets, and they could have environments and chemistry very different from Earth. This means that a sign of life on one exoplanet may not be a sign of life on another.

This poses a challenge for researchers studying exoplanets as it is difficult to be certain that a molecule detected in an exoplanet atmosphere was made by life. We cannot see life directly from so far away, and we also cannot travel to exoplanets to confirm findings. Because of this, there is (for now at least) always an element of uncertainty in interpreting spectral findings as evidence for life.

So, you think you found a biosignature

Detecting a signal with spectroscopy is just one step in the process. Spectral data are often messy, and even with careful analysis, a single detected feature could have multiple explanations.

To interpret a spectrum, scientists use models to decipher the chemistry of exoplanets based on what they know from objects within our Solar System and theories of planet formation. These models are then compared with the signals detected by our telescopes. However, some of the details in these models are so small, our current telescopes are unable to measure them.

Even with our most sensitive telescopes, it is difficult to differentiate a signal in a spectrum from background noise. To help decide whether to trust a finding, scientists use various mathematical tools. One such tool is known as 5-sigma. If a measurement meets the 5-sigma threshold, this means there is less than a 0.00006% chance that the finding is due to chance.

Matching a detected signal with a model of an exoplanet’s atmosphere is an iterative process. Even if a model and signal match, they must still be interpreted within the broader context of the exoplanet, taking into account other detected molecules and possible abiotic sources. This means biosignatures should not be seen as individual findings, but as a body of evidence interpreted collectively. Rather than a ‘Eureka’ moment, scientists will more likely find many small pieces of evidence that build over time and gradually point to a conclusion.

What is life?

Most methods for investigating life elsewhere in the Universe assume it will look like life on Earth (so called, life as we know it). So, to truly understand what we are looking for, we must also have a clear understanding of life on our home planet.

Life on Earth is full of surprises. Over the last fifty years, scientists have discovered organisms known as extremophiles thriving in environments once thought to be hostile to life. Extremophiles can be found making a home near deep-sea hydrothermal vents, beneath glaciers, and in caves far below the surface of the Earth.

Extremophiles offer examples of how life could survive in similarly harsh environments elsewhere in the Universe. However, extremophiles also challenge ideas about what life needs to survive. Most life on Earth depends on the Sun, either using sunlight to make food via photosynthesis or consuming organisms that photosynthesise. Certain extremophiles eschew sunlight altogether, instead using the chemicals from hydrothermal vents or surrounding rocks as a source of energy.

The diversity of life on Earth makes it difficult for scientists to have a clear definition of what constitutes life. Although there are many ‘working definitions’, there is no single agreed-upon definition that encompasses all of life as we know it. By studying life on Earth, scientists hope to gain a better understanding of what life is and predict what life could look like elsewhere.

What could life elsewhere look like?

When visualising life on a distant planet, it is easy to imagine plants and animals. But because of the immense timescales required for life to evolve, it is likely that if we do detect signs of life elsewhere in the Universe, it will be microbial life rather than little green men.

There is another challenge in searching for life elsewhere: what if it looks very different from any type of life that we are familiar with on Earth? There are theories that silicate-based life or life that does not require water could exist. If life takes an unexpected form, we might not even recognise signs of ‘life as we don’t know it’.

Astrobiologists are working on many fronts to investigate life in the Universe, seeking to understand the boundaries and conditions for life on Earth, investigating the possibility of life on other objects within the Solar System (such as moons) and searching the stars for indications that life could exist elsewhere.