The 30-year journey of European satellite navigation

In 2025, Europe celebrated the 30th anniversary of satellite navigation on the continent, a milestone built on decades of innovation, collaboration and excellence. Three decades of challenges and triumphs that have shaped the navigation systems we rely on today: EGNOS and Galileo, and that serve as legacy to building the satellite navigation systems of tomorrow.

At the European Space Agency (ESA), navigation activities were formalised thirty years ago. In October 1995, the ESA Council at Ministerial Level approved ARTES Element 9, initiating the studies and development of GNSS-1 (EGNOS) and GNSS-2 (Galileo). However, the first steps leading to this moment started as early as the 1980s, with pioneering research and studies conducted by ESA, national space agencies and European institutes.

Around the world, people were witnessing the rise of the American Global Positioning System (GPS) and its potential for civil applications. Based on a common understanding of its potential for Europe, ESA and the European Union joined forces to implement a European satellite navigation strategy in the early 1990s.

The first European venture

One of the first sectors to recognise the massive benefits satellite navigation (satnav) would offer was the civil aviation community. If satnav signals could be used at the highest level of reliability, they could also enable safe guidance of aircraft, which led to the concept of augmentation systems. In Europe, this materialised in the development and adoption of GNSS-1 or European Geostationary Navigation Overlay Service (EGNOS), the first of the two tracks roadmapped in ARTES 9.

For EGNOS to work, at least three transponders on geostationary satellites were needed. In 1994, ESA, the European Commission and Eurocontrol bid for two transponders that were integrated in Inmarsat III satellites. ESA’s experimental communication satellite ARTEMIS carried the third transponder.

In parallel, ESA and European industry began establishing the EGNOS ground segment and the system testbed for service demonstrations. By 1999, EGNOS successfully passed its Preliminary Design Review.

After years of initial definition, design, demonstration and deployment activities, the EGNOS system started transmitting its first test signal from space in 2003.

EGNOS was not only crucial on its own, but it also enabled Europe to build its industrial and technical expertise and to demonstrate its capabilities for an independent navigation system, which would become a reality with Galileo.

A joint effort

To guarantee coordination between ESA, the European Commission and Eurocontrol, the three partners signed the Tripartite agreement in 1998. Its mandate followed the development of EGNOS and included preparatory work for the definition and design of GNSS-2, which was soon renamed Galileo.

ESA’s team, then still part of the Telecommunications Directorate, wrote a programme proposal on how to bring the system they had been studying to life, under the name GalileoSat, reaffirming the cooperation with the European Commission.

Galileo was designed as a fully independent satellite navigation system with global coverage, compatible and interoperable with other satnav systems for the benefit of users.

Under GalileoSAT and through a series of preparatory studies funded by ESA, the European Commission and national agencies, key pieces of Galileo such as atomic clock development and design of the ground segment, navigation signals and orbits began to take shape. In 1999, the activities and teams had expanded to the level where ESA inaugurated its Galileo Directorate (now Navigation Directorate).

Demonstrating Galileo: a race against time

In 2003, the programme began to accelerate. The International Telecommunications Union (ITU) approved the frequencies requested for Galileo, setting off a countdown, as the concession would expire if unused by mid-2006.

Soon after, two demonstrator satellites were commissioned. SSTL in the UK built GIOVE-A, the first experimental satellite, in a record time from contract to launch in December 2005. GIOVE-A transmitted the first test navigation signal on 12 January 2006, securing the frequencies allocated by the ITU. The satellite also tested key pieces of hardware such as the Rubidium Atomic Clocks (RAFS) and studied the orbit’s environment.

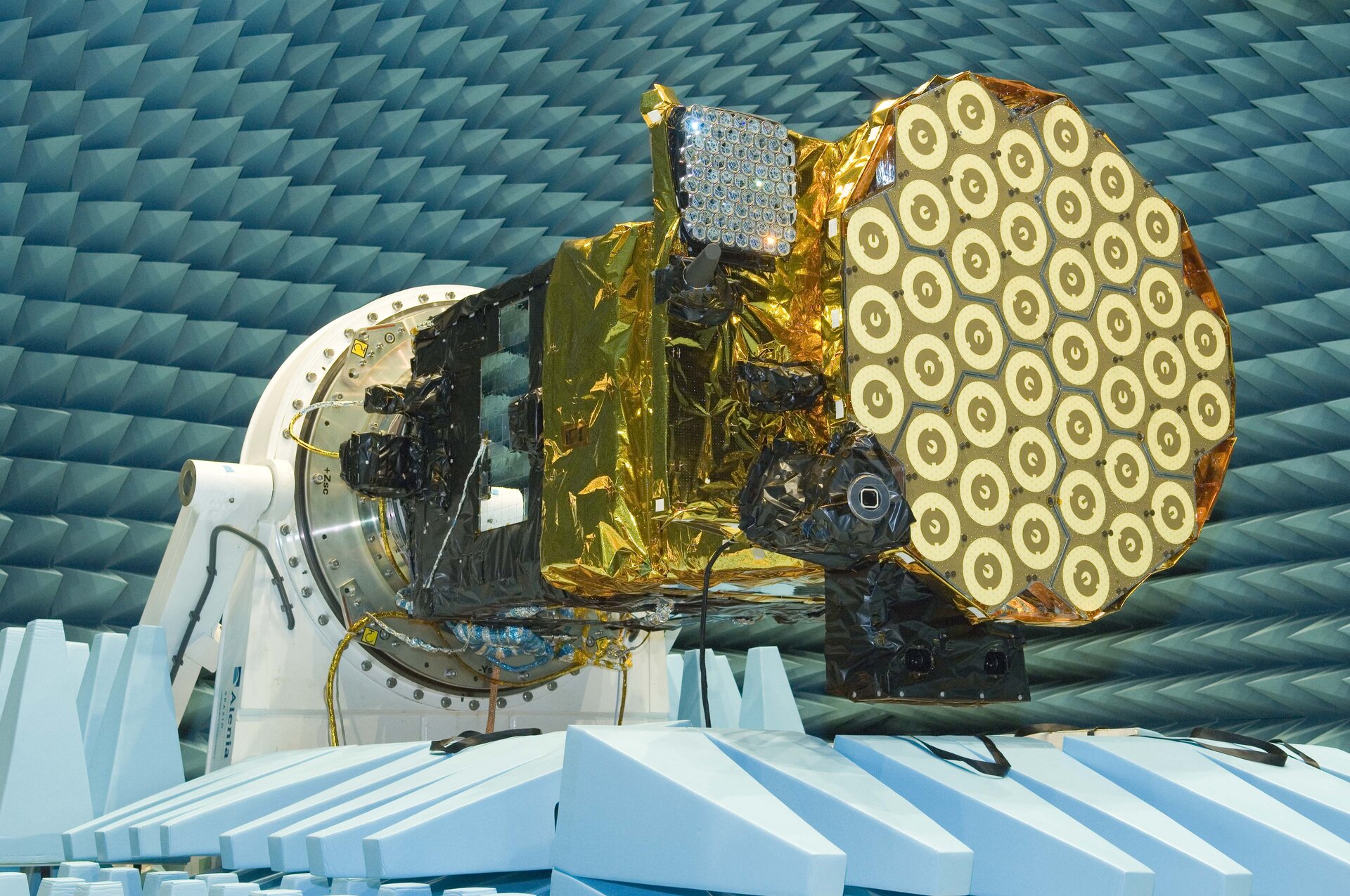

A consortium of major European satellite prime industries called Galileo Industries, and later EADS Astrium, built GIOVE-B. This satellite, launched in April 2008, was able to generate and transmit representative Galileo signals and flew for the first time a Passive Hydrogen Maser (PHM), the most stable atomic clocks in space and today’s Galileo master clock. GIOVE-B continued monitoring the orbit’s radiation and characterising the space environment of the Galileo orbit at 23 222 km, a completely new orbit for ESA.

Validating Galileo in orbit

After the system had been demonstrated in orbit, it was time to validate it. For that purpose, four satellites were needed (a receiver needs the signal from at least four satellites visible in the sky to compute its location). The four Galileo In-Orbit Validation (IOV) satellites were constructed by EADS Astrium and Thales Alenia Space.

The ground segment also continued to expand to support this next phase, with two control centres and a network of two dozen stations around the world.

In 2008, the European Commission decided to fully fund the Galileo programme, ending the Galileo Industries public-private partnership that had been established as the funding model for the programme in the early 2000s. ESA remained the technical arm of the programme, becoming the system development prime and design authority, responsible for the evolution of EGNOS and Galileo through dedicated research and development, a role that it still carries today. The European GNSS Supervisory Authority (GSA), established in 2004 and renamed the European Union Agency for the Space Programme (EUSPA) in 2021, assumed the role of service provider, also in charge of market development and user support.

The first two IOV satellites were launched in October 2011 and the second pair followed a year later. These launches marked a milestone in themselves as the first Soyuz launches from Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana.

With the four satellites in orbit, a historic moment took place: the first position relying entirely on European infrastructure. On 12 March 2013, the receivers in ESA’s Navigation Laboratory in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, were able to determine their longitude, latitude, altitude and time from the signals received from the four IOV satellites.

EGNOS: ready, set, go!

Meanwhile, EGNOS had been tested extensively on the road, at sea and in the skies around the planet and was now ready for public use. Operational responsibility was handed over to the European Commission and the European Satellite Services Provider (ESSP).

In 2005, the system began initial operations and on 1 June 2009, EGNOS officially entered service. The system was certified for use in aviation soon after, and in 2012 the EGNOS Safety-of-Life (SoL) service was declared operational.

Galileo begins serving the world

Already in 2008, during the in-orbit validation phase, the European Commission and ESA launched the procurement of the full Galileo system, including 30 satellites and a ground infrastructure with main control centres in Europe and a network of dedicated stations around the world.

OHB was hired as prime contractor to build the first batch of Galileo Full Operational Capability (FOC) satellites that would make up the full constellation of 24 satellites plus up to 6 spares, with SSTL providing the navigation payload. The same companies would continue to build the rest of the First Generation fleet, amounting to a total of 34 satellites.

At the height of production, a new Galileo satellite was rolling off the production line every six weeks. All of them were subjected to thorough testing at ESTEC, ESA’s technological heart.

Launches started rolling as well, after starting with a hiccup.

In August 2014, the first two FOC Galileo satellites were launched and stranded in incorrect orbits due to a malfunction in the Soyuz upper stage. A dedicated and perseverant team allowed the satellites to move to usable orbits for navigation testing and search and rescue operations. Beyond the recovery, this incident enabled the most precise measurement ever of Einstein’s theory on how gravity affects time.

To accelerate the deployment of satellites, Europe’s Ariane 5 launcher was modified to be able to carry four satellites at a time. Three launches, carrying four satellites each, between November 2016 and July 2018 boosted the constellation.

These intense years culminated on 15 December 2016, when the European Commission hit the red button marking the go-live of Galileo Initial Services. Galileo’s Search and Rescue services were declared operational at the same time. With the declaration of Galileo services, EUSPA (then the GSA) became responsible for providing Galileo services to users without interruption.

Galileo and EGNOS evolve

Galileo’s ground and space segment continued expanding. In 2021, two satellites were launched by Soyuz from Europe’s Spaceport; four more satellites launched from Kennedy Space Centre in Florida on Falcon 9 rockets in 2024 allowed the constellation to reach the number of operational satellites required to be considered complete as designed. At the time of writing, there are still four First Generation satellites awaiting launch.

New services have been declared operational since the start of Initial Services, making Galileo one of the most diverse satellite navigation service portfolios. The High Accuracy Service for dedicated receivers, active since 2023, delivers horizontal accuracy down to 20 cm and vertical accuracy of 40 cm. The Open Service Navigation Message Authentication started operations this year and allows a receiver to verify the authenticity of the signals, a crucial service to mitigate the threat of jamming and spoofing.

Galileo currently serves five billion users around the world, and while EUSPA is fully focused on service provision without interruption, ESA continues working on the system’s evolution to ensure it remains operational and serves evolving needs.

Twelve Galileo Second Generation (G2) satellites are under preparation, being built in parallel by Thales Alenia Space and Airbus Defence and Space. The satellites will integrate seamlessly with the current fleet. With fully digital navigation payloads, electric propulsion, a better-performing navigation antenna, inter-satellite link capacity and an advanced atomic clock configuration, G2 satellites will provide more robust and reliable positioning, navigation and timing.

EGNOS has been widely adopted by the aviation community and is now used in most airports in Europe. Since 2018, the evolution of the system, EGNOS V3, has been under development. It will also augment Galileo signals, becoming the first multi-constellation and dual frequency augmentation system, and is expected to enter service by the end of this decade.

Shaping the future of satellite navigation

Access the video

To celebrate 30 years of European satellite navigation, ESA opened the doors of ESTEC, its research and technology centre, in September 2025. Partners from across continents gathered for a sensational event that took the audience on a journey through time, honouring the achievements and collaboration that have shaped this story. The event aimed to acknowledge everyone who has contributed to Europe's success in satellite navigation while also looking towards the future.

Today, 10% of the EU’s GDP relies on satellite navigation systems, and downstream market has remarkable growth potential. With positioning, navigation and timing (PNT) data underpinning so many applications in our interconnected world, systems must not only be maintained but also developed and improved. ESA’s navigation programmes must address cutting-edge innovation that will drive their long-term evolution.

The Navigation Innovation and Support Programme (NAVISP) is supporting European industry to succeed in the highly competitive and rapidly evolving global market of PNT products and services. In the nine years since its implementation, the programme has gained significant traction, with more than 350 activities and hundreds of entities involved. The programme anticipated many of the ideas that are now being matured as ESA programmes.

In the years ahead, ESA envisions satellite navigation evolving into a flexible and powerful global infrastructure. Rather than relying on a single system in space, navigation will become a network of connected layers, combining satellites from different orbits, signals from the ground and information from onboard sensors, all working together in real time.

Celeste (formerly known as LEO-PNT) is a pioneering mission to enhance satellite navigation resilience and capabilities by deploying an additional layer of navigation satellites in low Earth orbit. The mission’s in-orbit demonstrator phase features a constellation of 10 satellites, with the first two set to launch in the first quarter of 2026.

The Genesis mission will contribute to a highly improved reference frame of Earth with an accuracy of 1 mm and a long-term stability of 0.1 mm/year, providing a coordinate system for the most rigorous navigation applications on our planet. The preliminary design review was completed in December 2025. Planned to launch in 2028, the Genesis satellite will combine the main geodetic techniques, synchronising and cross calibrating the instruments to determine biases inherent to each technique, allowing them to be corrected for superior precision.

ESA’s Moonlight programme aims to become Europe’s first off-planet telecommunications and navigation provider, creating lunar versions of essential Earth-based services. This will unlock the potential for future lunar missions, enabling high data rates and low latency, improving landing and navigation capabilities and reducing on-board complexity. The first step in this programme is Lunar Pathfinder, which is set to begin operations in 2026.

Recently, ESA's Council at Ministerial Level in 2025 funded three new navigation missions: OpSTAR, NovaMoon and Future PNT demonstrators. OpSTAR will demonstrate in-orbit how optical inter-satellite links can enhance PNT through precise time transfer and ranging between satellites. NovaMoon will enhance Moonlight navigation services as the first station on the Moon for high accuracy navigation. Future PNT demonstrators will allow early development of new technologies that could transform the future PNT landscape. As a part of the FutureNAV programme, these missions will mature and demonstrate promising system concepts and upstream technologies for institutional and commercial use.

Several technologies have been identified as main drivers for the future of PNT: resilience, robustness and autonomy against interference, optical and quantum technologies and sensors, integrated navigation and communication, 5G/6G Non-Terrestrial Network (NTN) solutions, disruptive technologies to enhance flexibility such as Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence, new integrity concepts and new signals, and much more.

Satellite navigation is entering a new era, one that promises to change how we move, connect and understand the world around us. For ESA, the future of navigation goes far beyond providing positioning. It is about creating intelligent, resilient systems that help society function with greater safety, efficiency and autonomy.

Building on our legacy to shape the future of positioning, navigation and timing.

Explore Europe’s Journey in Satellite Navigation through the book soon available in print at the ESA Shop and stay tuned for the release of the documentary.