What types of comets are there?

In essence, all comets are clumps of ice and dust. When they fly close to the Sun, they heat up and spew out gases and dust, enveloping the solid nucleus in a large hazy cloud called a coma and often producing one or more lengthy tails. We classify different types of comets based on their flight path through space.

Comet origins

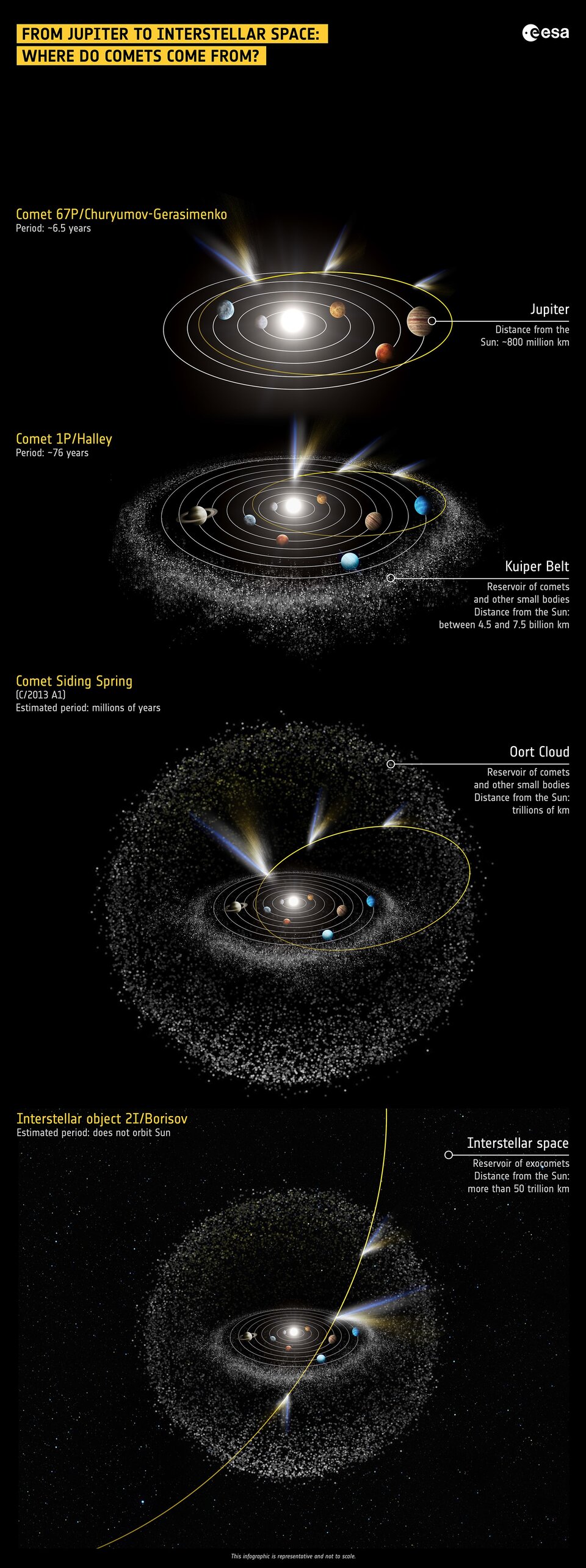

Comets are icy remnants from the birth of the outer planets in our Solar System. They lost the gravitational tug-of-war to the larger planets and were kicked out to beyond the orbit of Neptune. Today, comets are thought to come from two massive reservoirs in the Solar System: the Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud.

The Kuiper Belt is a ring of icy objects that starts beyond the orbit of Neptune. Its largest known inhabitants are the dwarf planets Pluto and Eris. The Oort Cloud is an enormous spherical cloud lying hundreds of billions of kilometres beyond the outermost planets.

From these reservoirs, comets are flung back towards the Sun by the gravitational tugs of passing stars and other objects. Most comets approach the Sun in highly elliptical orbits. These bring them close to the Sun but also extend far outwards, hinting at their origins. The Oort Cloud is so far away that it has never been seen directly, but its existence explains why many comets enter the inner Solar System at large angles from the planetary plane.

Some comets fly round and round

Short-period comets whizz around the Sun in 200 years or less. A well-known example is Comet Halley, which has an orbit of around 76 years. The comet is named after Edmond Halley, who showed that the comets seen in 1531, 1607 and 1682 were one and the same, and correctly predicted that this comet would next appear in the sky in 1758.

Comets with a period less than 20 years are typically called Jupiter-family comets. Their orbits tend to lie close to the planetary plane, not far from Jupiter’s orbit. Their flight paths are often strongly affected by the gravitational pull of Jupiter and other planets. Comets with a period between 20 and 200 years are also called Halley-type comets. These orbit the Sun between the orbits of Jupiter and Pluto, coming in at any angle from 0 to 90 degrees from the planetary plane.

Many of the earliest comets we observed were sungrazing comets, which light up brightly thanks to their extremely close approach to the Sun. This is a risky trajectory that comets don’t survive for long. Sungrazers all eventually break up into smaller pieces, or even evaporate completely. When Earth passes through a trail of cometary debris left behind by a comet, we are awarded with a beautiful shower of meteors or ‘falling stars’.

Other comets are infrequent visitors

There are other comets that rarely visit the inner Solar System. Long-period comets have orbital periods from 200 to more than a million years. We have detected some passing by, but we’ve never gotten close to one. ESA’s Comet Interceptor mission is the first that hopes to get up close and personal with this more pristine type of comet.

Not all comets are periodic: some comets’ flight paths aren’t closed orbits at all. If they acquire enough speed from passing by a planet, normally Jupiter, they can escape the Sun’s gravity and fly out to interstellar space, never to return.

Other objects fly through the Solar System with such speeds that they can’t have formed in the Solar System to begin with. This was the case for 1I/‘Oumuamua and 2I/Borisov, which flew through our Solar System in 2017 and 2019, respectively. These interstellar objects were most likely exocomets: comets that formed at a star other than the Sun.

As a final note, the exact distinction between different types of objects in space isn’t always clear-cut. Whether or not something is classified as a comet, rather than an asteroid, usually depends on whether it is seen to spew out gases and dust, enveloping the object in a coma. However, some objects, like those that live in the Kuiper Belt, never get close enough to the Sun to develop a coma. Closer to the Sun, active asteroids (sometimes called main-belt comets) fly on near-circular orbits among the asteroids while releasing dust and gases like you would expect from a comet.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland