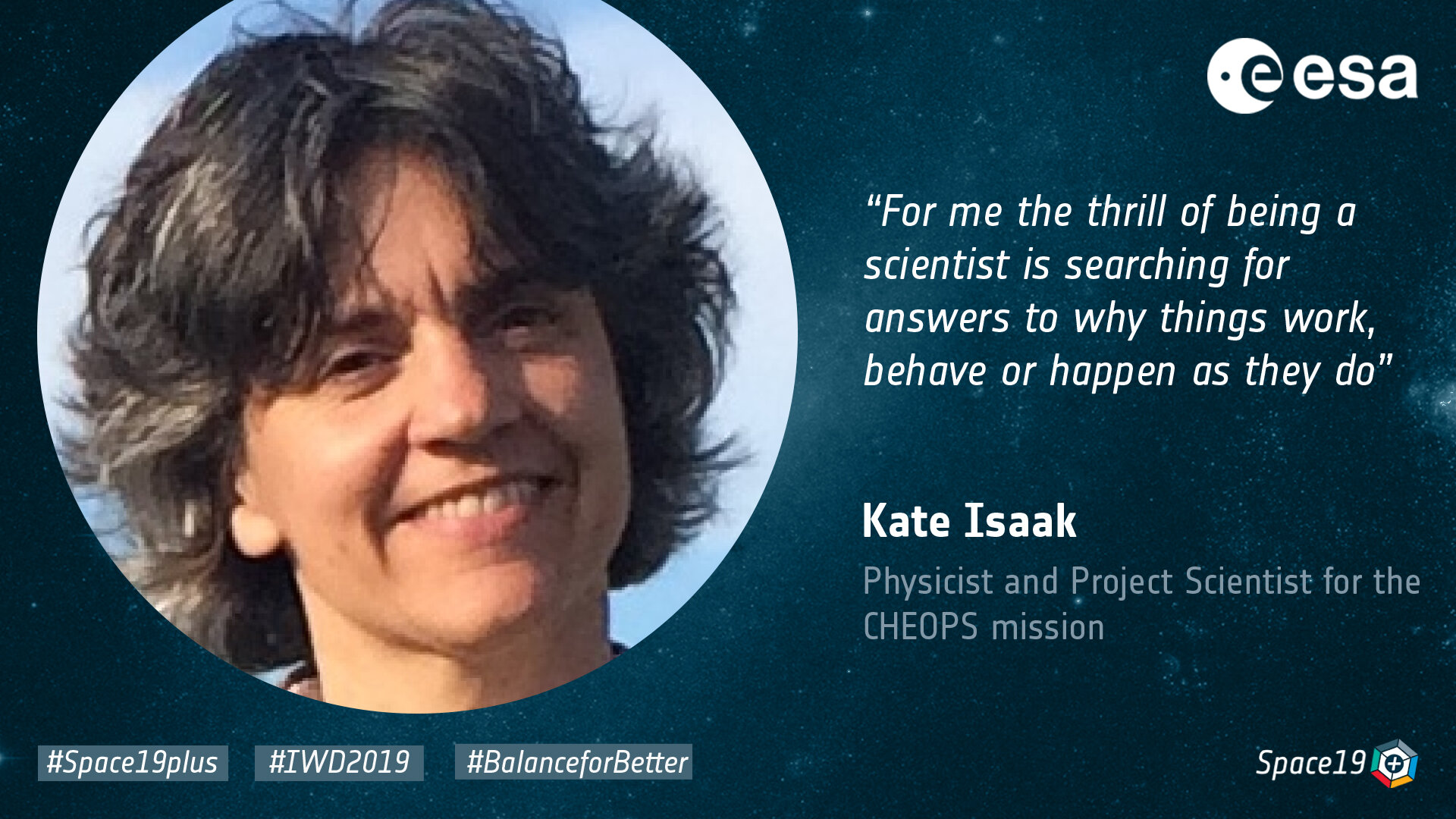

Kate Isaak, ESA CHEOPS Project Scientist

Please give a brief description of your duties at ESA.

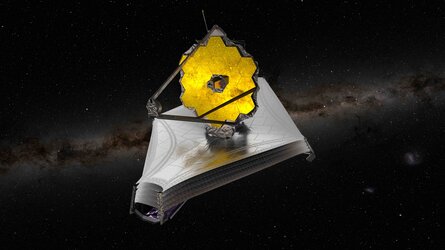

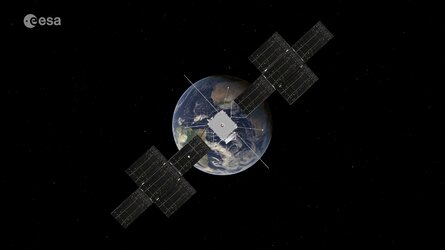

I am a physicist working as the Project Scientist for the CHEOPS mission – Characterising Exoplanet Satellite. CHEOPS is a satellite/science mission that will launch later this year and that will measure precisely the sizes of small exoplanets, specifically planets that are known to orbit bright, nearby stars other than our own. I am based at ESTEC, the European Space Research and Technology Centre in the Netherlands. As project scientist, I am responsible for the scientific management of a science mission at ESA, and have the job of trying to maximise the science return from the mission. This takes many forms, from working on the detailed definition of science requirements all the way through to ensuring that the community has enough technical information to be able to use the satellite to propose and plan their own observations. My job has many different aspects to it, and enables me to use a wide range of the scientific and technical skills that I have picked up and developed over the years. And I am also able to do a bit of science!

I have been at ESA for nine years, almost to the day – time that has flown by ‘en grande vitesse’. In that time, I have worked on three different missions or mission studies. CHEOPS will be the first of my missions to actually be launched. Let’s see what the autumn brings!

Did you encounter gender barriers on your way to becoming a scientist / engineer?

I have been very fortunate and have not experienced any barriers. My parents were both scientists so, to me at least, there was never anything particularly special or different about being a scientist. I never felt it was something I shouldn’t be able to do or that was out of reach – they clearly did it, so why shouldn’t I? At my high school – a mixed state school in the UK – the teachers always encouraged girls and boys equally. In the last years of high school, there were even more girls than boys in my physics class, something that changed dramatically at university, I have to say! There, I was in a women’s college at a large university in the UK. During physics lectures, women were definitely in the minority. At the college, however, I had the most amazing supervisors in physics, chemistry and biology. Some of them were women, but not all. My director of studies, Owen Saxton, was exceptional – adopting all those doing science in the college – encouraging us to believe in ourselves, providing extra tutorials and, together with his wife, arranging the essential cups of tea and cakes for us when things got stressful.

What inspired you to pursue a career in science and engineering and what motivated you to join ESA specifically?

Ever since I can remember, I have been interested in the natural world, wanting to know the answer to the question ‘why?’ – why something works, behaves or happens as it does. For me, science provides many answers (as well as raising many more questions), and if not ‘the answer’, then a framework and methodology to try to understand more. For me this is a big part of the thrill of being a scientist. Since finishing my studies, I have worked at the interface between science and engineering – wanting to build, or be intimately involved in the development and building, of the tools needed to answer scientific questions that were of deep interest to me. Just before moving to ESA, I was working in Wales as part of a team studying the contribution by ESA Member States to a Japanese-led Space Observatory called SPICA. Our work covered many topics and disciplines, challenging the current understanding of galaxy formation and evolution, piecing together some of the puzzles of star formation, planning the best strategy to pack the many observations needed to answer the scientific questions into a few years of observation time, while pushing the capabilities of state-of-the-art detectors and puzzling over which were the essentials and nice-to-haves in our suite of instruments. This was all done in a multinational team spanning more than a dozen European countries, Japan and the US, and involving dozens of institutes and universities. I was extremely lucky, and a position came up at ESA to work in the same stimulating and dynamic multicultural and multidisciplinary environment at exactly the time that I wanted to try to move a little closer to my husband-to-be, who was then working in Germany. I applied. I was in the right place, at the right time, and with some more good luck, I am where I am today.

What advice would you give to a girl or young woman who is considering a career in science and engineering?

The old English saying "nothing ventured, nothing gained" definitely holds true. Follow your heart, believe in yourself. Doing science teaches you to think critically and analytically and to tackle problems systematically, skills which are not only invaluable in technically oriented disciplines but that are essential in all walks of life. It opens doors to opportunities that you may not even know that exist. If you are interested, and you are willing to work hard, go for it and good luck!

I think women are not yet as good at networking as men. There are also not as many examples of women in the many different types of jobs that you might be considering. Don’t hesitate to contact women who are in the sorts of jobs that you think you might be interested in. Ask them for advice and tips. It won’t work every time, but again, nothing ventured, nothing gained.

Germany

Germany

Austria

Austria

Belgium

Belgium

Denmark

Denmark

Spain

Spain

Estonia

Estonia

Finland

Finland

France

France

Greece

Greece

Hungary

Hungary

Ireland

Ireland

Italy

Italy

Luxembourg

Luxembourg

Norway

Norway

The Netherlands

The Netherlands

Poland

Poland

Portugal

Portugal

Czechia

Czechia

Romania

Romania

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Slovenia

Slovenia

Sweden

Sweden

Switzerland

Switzerland